(written after the film’s rough cut)

The First and Last

The second rough-cut screening of Me and My Condemned Father (我的爸爸是死刑犯) took place at Tò-uat Books in Taipei on January 17, 2025. Tò-uat Books is a place inextricably linked to human rights issues in Taiwan. It is where different lectures and screenings on social issues are regularly held, and various NGOs have long considered it an essential and central hub for advocacy campaigns and a breeding ground for civic movements. Intentional or not, it was undoubtedly fitting for Lee Chia-Hua (李家驊) to host his rough-cut screening there.

Ten months ago, I met up with Lee and his film crew at the Kaohsiung Second Prison in Yanchao (hereinafter referred to as the prison). He was shooting the film’s final scene that day. More importantly, according to Lee, this would be his last documentary film. I wasn’t entirely clear on what the film’s final scene would look like, but since he told me so adamantly that this would be his last documentary, the ending scene of the film was probably something he had long thought about.

Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained

Filming inside a prison can be quite daunting because each facility has its own rules and requirements. They can come up with different reasons to reject a request, regardless of what human rights issue you are advocating for or the justice you are seeking. Prisons can aggressively or passively refuse a request based on their considerations, as these are not places that should be easily accessible to the public. Additionally, prisons are widely recognized as a place of captivity for criminals, and criminals are not supposed to enjoy the same rights as regular citizens. People are incarcerated to take responsibility for the crimes they’ve committed and to work towards rehabilitation; therefore, they need others to supervise, educate, guard, and manage them. Moreover, since Lee was requesting permission to visit and film death row inmates, the situation was even more stringent. If a biased opinion were expressed, the interview could lead to unfavorable consequences for the prison, its administrators, and the governing authority. Consequently, applying for permission to film inside a prison often requires a lengthy process. I’ve also recently filmed inside a prison, so I completely understand the complexities behind the process and the anxieties that may come with preparing for such a filming endeavor.

On that day, the film crew consisted of two camera operators and Lee, and three subjects were arranged to be filmed. As both the film’s director and producer, Lee had to communicate what needed to be filmed with the camera crew and also confirm various details with the prison authorities, including the equipment they had brought and their personnel, as well as which areas could be filmed and which were off-limits. Lee had to handle all these pre-production tasks personally, as he was the liaison and the only one who could oversee the entire production. However, during the actual filming, this way of working also meant that he was constantly interrupted and called out of the scene, sometimes just to confirm the most trivial details, which forced him to hastily switch from his director role to that of a producer.

“It’s not that I don’t wish to have a producer, but the budget is really tight. I don’t want to exploit anybody, so there’s no choice but to exploit myself; however, it really is troublesome,” said Lee.

Indeed, due to budgetary constraints, documentary filmmaking in Taiwan often involves limited production personnel. Sometimes, a director would also have to be the film’s producer. However, it’s relatively uncommon because most directors prefer to focus solely on the film’s creative aspects. With limited budgets, many directors typically also work behind the camera, which allows them to keep their focus on the actual filming rather than off-set matters, since the two entail completely different professional and practical demands.

Strictly speaking, Lee was not working completely without a producer, but as he said, due to a tight budget, he couldn’t hire a full-time producer to help him from start to finish. The producer he was working with for this film joined the production after filming was completed, so the producer’s focus was mainly on post-production, editing, distribution, and marketing tasks. From this arrangement, it was apparent that Lee, ever the diligent worker, was accustomed to taking on a significant amount of work himself.

Site inspection was scheduled for that morning. The scheduled filming would take place in the afternoon after the site inspection. As we handed over each piece of filming equipment, the prison guard carefully checked to see if the pieces matched the previously submitted list. After placing our phones into individual locked boxes, the iron gate leading to the heart of the prison opened. The first thing we saw was a Greek Mediterranean-style color scheme and a decorative windmill. A small stream flowed steadily beneath a transparent plastic cover, and a solemn statue of Guanyin was placed against the blue and white backdrop. Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion who helps those in despair, was set in a romantic and relaxed Mediterranean atmosphere. Ironically clashing? Sure. However, in prison, who isn’t hoping to be saved and to leave the tiny iron cage, but does leaving this cage mean they will follow Guanyin and transcend beyond this world to a pain-free, sickness-free state of oblivion, or will they return to society and physically reconnect with the mortal world? This is something that none of us knows the answer to, especially for the subjects of Lee’s film. As death row inmates, they have no idea, and they can only wait until the moment their cell door opens to find out where they will be taken to.

The filming in the prison was divided into three parts: standard visit, special visit, and filming of the inmates’ living spaces. Given their similarity to typical portrayals in various drama productions, the standard visit is relatively easy to imagine: taking place behind iron bars and a glass panel, the two parties communicate through telephone receivers, attempting to convey practical messages and emotional feelings through this sole line of communication. The special visit, on the other hand, allows both parties to sit at a large table to talk without any cold, impersonal barriers standing in between. Of course, there will be prison staff monitoring nearby, and handcuffs and shackles may not be removed. However, this type of visit is rarely permitted. Except for special holidays or with special permission, many prisoners may never be allowed this type of visit. As for filming the inmates’ living spaces, this included their cells and the areas to which they are permitted to go during the time out of their cells.

Family reception center at the Kaohsiung Second Prison (photo courtesy of Chang Ming-Yu)

The filming that day involved three subjects—a father and his two sons. They were casually chatting in the reception room for special visits, paying no particular attention to the camera and the crew at the side. They seized the opportunity to look at each other and say what was on their minds. The words exchanged were of no particular importance, mainly involving the father giving his sons various reminders, such as not to drive too fast or squander money, the kind of typical advice one would get from their elders in an Asian family.

“I had planned the things that I wanted them to talk about, but after watching them chat, I then decided not to dictate the situation and just let the three of them talk freely,” said Lee.

For the filming that day, it was apparent that Lee had planned ahead of time what to shoot. Before filming started, he had discussed and assigned tasks with the camera crew, including scenes in the special visit reception room, standard visit procedures, and even scenes of the inmate’s sons sending in food and money. Everything was already rehearsed in his mind. However, during the actual filming, he was not adamant about following his original vision; instead, he stepped aside to let things unfold naturally, without making any interjections. The only thing he did was help divert interruptions from prison staff during the conversation between the three subjects, allowing the camera crew and the subjects to carry on with what they were doing or saying in a safe and relaxed space. At that particular moment, the organic and natural qualities of documentary filmmaking, a topic that has long been discussed, were fully evident.

Filming outside the Kaohsiung Second Prison (photo courtesy of Chang Ming-Yu)

The Rough-Cut Screening

At the rough-cut screening, Lee introduced the film’s editor, Chen Hui-Ping, to me, and he then proceeded to the following table to discuss the film’s ensuing marketing and distribution plans with the post-production producer. Chen, who’s younger than Lee, studied at the same graduate school as him, and the two have collaborated before. Although Chen has experience as a documentary director, she primarily works as an editor; in her own words, being an editor is a more suitable and comfortable position for her.

Lee had initially told me that he had reserved six months for editing, but the schedule had been extended by over four months at that point. I began by asking Chen about this. The rough-cut version being screened that day was 150 minutes long, but before this, they had a four-hour version. They were hoping to further shorten it to around 120 minutes at that point. The purpose of the rough-cut screening was to invite everyone involved in the film to watch it and provide feedback. This was also the first rough-cut screening that Lee had organized for his own films.

“There are a lot of talking head interviews in the film; sometimes I would put the footage down for a while before resuming to edit,” said Chen.

To condense the film from four hours to 150 minutes, editing it seemed like a straightforward approach, but the large amount of interview footage required careful consideration of what to keep and what to cut—a process that had to rely heavily on the editor’s and director’s experience and perhaps a degree of objectivity. I often think that most documentary filmmakers must have a genuine affection for the subjects of their films, as they seek to express their own thoughts and show what they want to be seen through those subjects. This was probably true for Lee; he has always been very considerate of his subjects. So, for him to be coldhearted enough to edit out some of those lines was an enormous undertaking, both internally and externally.

Chen said that she wanted to use the rough-cut screening to gather everyone’s feedback and take a step back for a bit, because when an editor gets too close to the film, things can get complicated. Just as she was saying that, Lee abruptly turned to our table and said, “This is my favorite film out of all the films I’ve ever made. It’s truly my favorite. Nothing else can compare!” He was beaming with confidence and made Chen and me, who were just contemplating the next step to take, chuckle. It was obvious to me that Lee was speaking from the heart; his gesture and expression made it clear that he wasn’t just trying to liven the mood.

Post-Screening Observation - I

After the 150-minute screening, which took us back through time, the attendees took a brief break and walked around before naturally forming a circle, much like a book club. Based on their respective roles, people then began to share their thoughts and feelings about the film.

The screening’s attendees included not only the documentary’s film crew but also representatives from groups related to the film’s subjects and their rights. Therefore, the feedback provided was not primarily focused on improving the film’s visual appearance, nor was it narrative-oriented; instead, a lot of them offered reminders. The reminders included whether the subjects’ words might be taken out of context and misinterpreted or misunderstood by the audience, or whether certain footage of the subjects’ living and work situations might raise public concerns or legal issues due to small details that were overlooked.

Based on my observation, these reminders stemmed from the fact that the awareness and response to the film’s topic have yet to achieve a consensus in today’s Taiwanese society. Politically, morally, or in terms of judicial human rights, it is an issue that those in power are unwilling to confront or resolve. Consequently, whether to abolish capital punishment or not remains a topic of controversy, division, and polarization in public opinion, and the situation has also become an effective tactic for those with vested interests.

Therefore, the individuals involved, who are also the subjects of this film, are constantly harmed throughout the process, whether they are on death row or the families of the incarcerated. Especially for some individuals who happen to be family members of both victims and perpetrators, at a particular stage in life, they would have to start to endure such harm, and through time, the harm would be accompanied by a lack of understanding and even ill-intended stares from others. They would never heal from that kind of hurt, and all they can do is to allow layers upon layers of scar tissue to form and numb their pain temporarily. Therefore, I believe that the intention behind those reminders from our friends at the screening was to prevent the film’s audience from triggering those who have already suffered by reminding them of their wounds.

Documentary filmmakers use film to reflect in an artistic manner, with the filmmakers’ true intentions conveyed through the actions and words of their subjects. However, their subjects would often entrust themselves wholly to the filmmakers, but how the filmmakers use and handle the footage can inadvertently place the subjects in a position where they are directly confronted by the audience, leading to criticism, doubt, and misunderstanding. This is something that has always been the most unavoidable yet common issue faced by documentary filmmakers during their creative process, even for the most experienced directors. This was something that Lee and I had repeatedly talked about when I was there to observe his filming process.

Post-Screening Observation - II

I recall the first scene in the rough cut showed three of the film’s subjects in a quiet and safe space. They were having some snacks and about to start talking. After some small talk, their conversation turned to a serious but unavoidable topic: “If he’s released, should we take care of him?” This “he” is an absent, non-existent figure, a seemingly blank, or perhaps a ghostly presence that has infiltrated their lives.

Whether to take care or not involves conflicting values that pull and tug; family obligations have always been an inescapable lesson in life for ethnically Chinese people. From childhood to old age, each stage of life presents its own challenges that one must confront. Parents bestow life upon their children, bringing them into this world, and then do what they can to nurture them, enabling them to grow into adults.

There’s an old Chinese proverb that says, “parents always have their good reasons.” Even if a parent has made countless mistakes, the bottom line is that parents are the ones who gave their children the opportunity to become independent adults. Even if a parent has made mistakes, shouldn’t we still accept them? As children make mistakes throughout their lives, their parents are there behind them as their strongest support. Besides, the notion of “a lack of filial piety” is so cumbersome and devastating that it’s probably best never to be associated with such sentiment at all. However, when parents make mistakes, it’s not just them who are affected; the entire family, including the children, gets dragged into it, leading to a broken family with financial struggles, neglected education, and childcare problems. As the children finally become adults and are capable of pursuing the kind of life they want and look for the type of partner they wish to have, if they are forced to confront the very factor that once forcibly altered their lives, all in the name of familial obligations, then those dreams of pursuing what they want in life might vanish into thin air. Is there truly no other way? Must they ultimately succumb to the ever-so elusive “destiny?”

Opening with a question that presents valid arguments on both sides, the film then shows snippets of the lives of the two main subjects, interspersed with extensive conversations between them, each prompted by a series of open-ended questions that allow them to speak freely. The scope of these questions is quite broad, spanning from issues of identity to recollections of that non-existent “he.” Through the seemingly unrelated questions, they talk in an everyday, casual manner. Particularly intriguing moments occurred during breaks between the series of conversations, when the subjects would relax and take a smoke break on the balcony. However, the words they exchanged during those brief intermissions were unreservedly recorded by the microphones clipped to them. The words exchanged felt like natural extensions of the interview questions, yet their relaxed state made them more candid and honest. Even though their faces weren’t filmed, their genuine thoughts were earnestly conveyed through the tone and pace of their speech. At the same time, Lee’s “eavesdropping” was entirely captured by the camera. Calling it eavesdropping might be a slight exaggeration; it felt more like he was trying to grasp what was on their minds. Even with a considerable sense of trust, striving to be more empathetic than expected has always been a goal every legitimate documentary filmmaker desperately strives for in their work. At least that’s how I see it.

At the rough-cut screening, one of the film’s subjects, A-Hsiu, was sitting next to me, and I couldn’t help but observe his reactions as he watched the film. Particularly during the scenes featuring his father, my attention was fixed on A-Hsiu. Was I expecting a specific reaction? Not really. I just wanted to see how he would react to watching that familiar stranger, someone he’s connected to by blood, but who he could only see on a screen. On top of it all, he was also in a strange environment surrounded by unfamiliar people.

I saw him giving a faint smile at times, and at other moments, he would let out a sigh. These were things I, sitting beside him, could clearly see and feel. Particularly when his father repeatedly expressed his desire to end his life, both during the interview and in real life (he has attempted to end his own life), this was stemming from the unbearable torment within his physical shell and a profound despair about life itself. As his child, how should he confront this? I’ve thought about this many times, but I’m still unsure about which perspective to take.

A Camera person quietly capturing an everyday scene (photo courtesy of Chang Ming-Yu)

The film concluded with A-Hsiu and some friends watching fireworks on New Year’s Eve. A-Hsiu’s gaze was fixed on the sky that was illuminated by the string of dazzling fireworks. For me personally, those sparks of fireworks in the film hold multiple meanings: one is the sparks of life’s unyielding resilience, and the other is the gunfire that could liberate someone from this life. The reason behind these thoughts is perhaps due to something that’s deeply rooted within me, and it’s related to my own father. My father once served as an execution prosecutor at an execution site. His role involved final verification of the identity of death row inmates and listening to their last words before their execution. His work and the scenarios carried out at the execution site became my bedtime stories. When the image of fireworks appeared in the film, my mind immediately made this connection. But if I could, I would also like to find out what was on A-Hsiu’s mind when he saw those fireworks.

A Documentary Filmmaker’s Final Question

Through this opportunity of writing down my observations, I was able to properly ask Lee questions about documentary filmmaking, rather than being limited to just one particular topic.

“I always think about being more coldhearted and keeping my distance from the film’s subjects after shooting, but I’ve failed each time. There’s always this sense of being indebted to them, because I’ve gained so much from them while giving so little in return. Whenever I think about how to repay them, I realize it’s impossible. This is why I think I’ll quit documentary filmmaking after finishing this project. The emotional labor involved is just too much,” said Lee.

Since 2012, whether working on personal documentary projects or commissioned cinema releases, Lee feels that he has been repaying past debts. Though the topics explored would be presented to him, they’re actually ripples from what he has done previously. One ripple would stir up another, interconnected yet also restricting him. Therefore, this is his proclaimed final documentary, a decision he made after turning 45, as he seeks to be self-indulgent for once and prioritize himself a little more. This is grounded in the principle that being a person matters more than filmmaking.

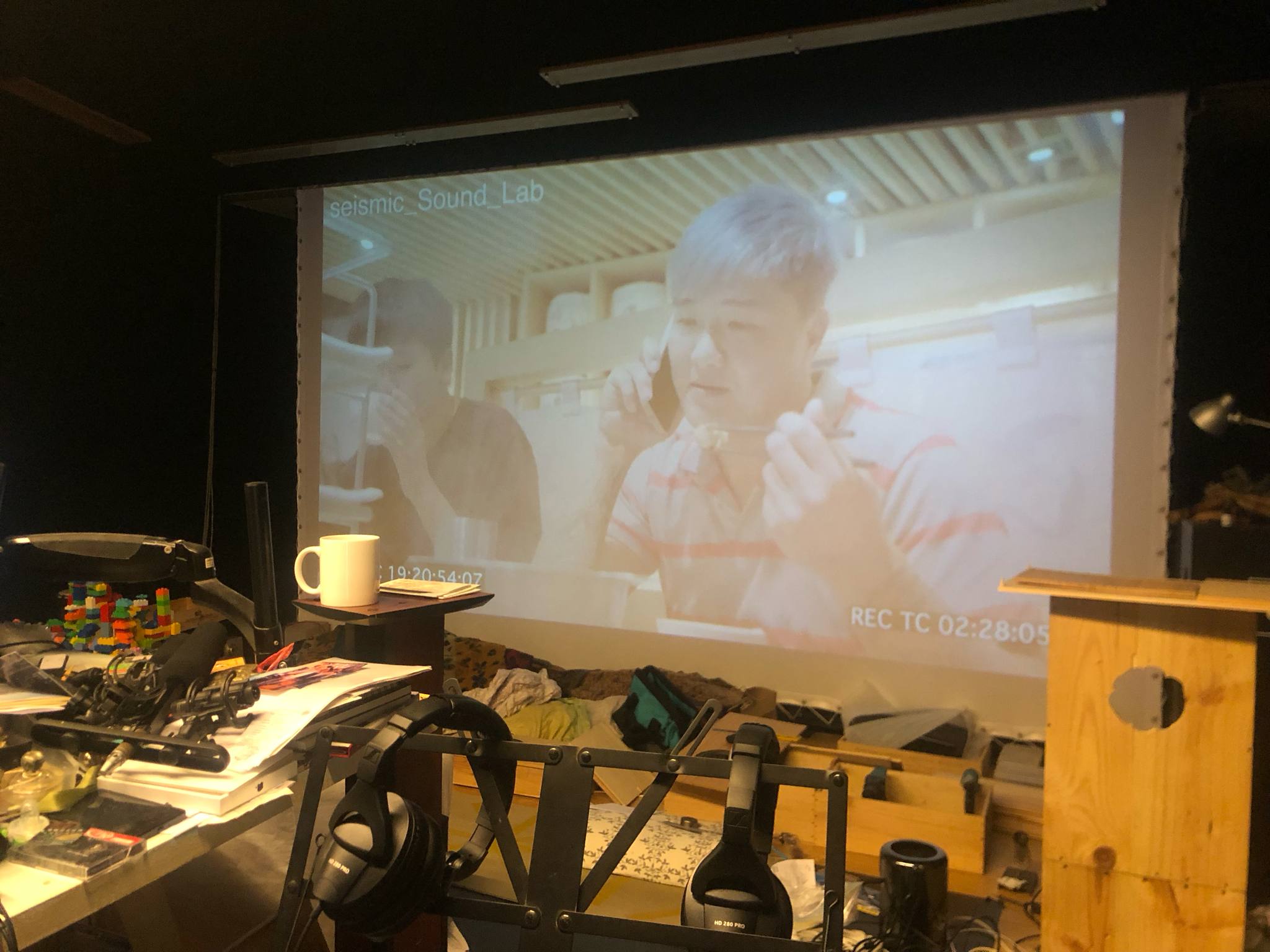

Post-production mixing of Me and My Condemned Father (photo courtesy of Lee Chia-Hua)

This reminds me of journalist Hu Muhchyng’s Facebook post from February this year, which was a month after Lee’s rough-cut screening. Hu posted on Facebook thoughts extended from her book, A Sketch of a Female Serial Killer (一位女性殺人犯的素描), which was published last year. The post included thoughts on the distinction and logic between private and public writing styles, as well as interactions and observations she’s had with her past subjects, delving into her own perspective and viewpoints, exploring how those issues and individuals have impacted her life and her perception of the world. After taking my time to read what she had written carefully, I then scrolled down to read the comments below and saw the following short comment by Lee: “Such invaluable reflection and reminder. I feel grateful to see this at this particular moment. (It seems to confirm further what I’m not suitable for, and it’s probably time to say goodbye for real.)”

Post-production mixing of Me and My Condemned Father (photo courtesy of Lee Chia-Hua)

Although I didn’t personally ask Lee whether that statement reflected his current thoughts on documentary filmmaking, given that I’ve known him for quite some time and have observed his work for more than a year, it was easy for me to make that connection. Perhaps it was fate that, as he pondered on exiting, a fitting commentary was presented before him.

Doing creative work inherently entails some dogged willfulness; yet, observing Lee’s doggedness, I see it not as self-indulgence, but as this phase comes to an end, he can now return to the very essence of documentary filmmaking: being accountable only to his subjects and himself. As he turns his eyes away from documentary films for now, any other looks from other people can also be shuttered for now. May we one day be like him, too.

*Translator: Hui-Fen Anna Liao

More CASE STUDY

_1685344611325.png)