After learning about the artist roster of Shattered Sanctity, I first thought it seems to be an attempt to gather and sort through a group of young artists with a specialized concentration in “project-based art”. After reviewing the original content proposal, many of the artworks include results of field research, with emphasis placed on specific textures of society. Yi-Hsin Nicole Lai’s curatorial practice that concentrates on local places is aptly revealed by this selection of artworks. Lai has been actively engaged in a city-oriented residency project in Tainan, where she forms a curatorial connection with the local area; however, Tainan, home to an active contemporary art community with a rich grassroots cultural background, is quite different from Taiwan’s metropolitan capital city, Taipei. With the differences between the cities and also working with a group of relatively young artists, what kind of “local” connections can Shattered Sanctity incite? Furthermore, what kind of response can this curatorial project, which imaginatively focuses on Japanese colonial architecture, make towards “such collective sanctity [which] has become a shared historical reference or shattered fragments carried by individuals”? When both the individual and the collective are bound to be dispelled by modern urban space’s dual tension that places value on history while also leaning towards de-contextualization, “[t]he collective sense of history created by the shattered sanctity might not disappear very soon, but it will gradually lose the ability to interpret the collective sanctity”; how then can it transpire into the curatorial consciousness of Shattered Sanctity?1

Wood Shack No. 1 located on the square of MoCa Taipei (Photograph by Huang Ling-Jun, courtesy of Art Square Taiwan)

Regarding Site Selection

Thoughts evoked by this string of questions appear to twist and turn, endlessly – imagine a person using a twig to stir up cascading ripples on a calm and still lake. When the ripples prompted by the temporary churning reached the shore, they are then diverted back. In observing these interlocking ripples, such change to the environment impelled by human intervention can spark complex thoughts – Although the environment remains essentially unchanged, a rather intimate relationship appeared to have been formed between humanity and the environment. Taipei is a city that has nurtured and sustained me for over 40 years; therefore, I have a profound understanding for the experience of gradually losing the ability to interpret the collective consciousness that has emerged in this city; it is a feeling of slight helplessness, it is also hard for one to fully show concern for. It is an experience that is similar to relocating to a different city for work, which in the beginning may make one feel alienated and detached from their surroundings and nearby communities; however, some familiarity can usually soon be realized in the strange city, and by mixing together spatial experiences one holds for the old and new places, a comforting sense of belonging can then be discovered.

This comforting sense of belonging is likely in a position that shifts away from history or is against “History with a capital H”; Lai references In the Metro by Marc Augé, which proposes that History “with a capital H: the history of others perceived for a moment as the history of everybody.”2 However, compared to the French anthropologist’s viewpoint, for those of “us”, isn’t this process of perceiving the history of others as the history of everybody the colonial imprints that the European empires have left in local places since the 19th century? Therefore, if we were to refer to this concept of the history of others as a collective history when considering the chosen venue of Shattered Sanctity, an awkwardness that is unique to Taiwan would immediately arise – It has chosen to show in the European-style classical building of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MoCA Taipei), which was an elementary school built for children from mainland Japan during Taiwan’s Japanese colonial period. After the end of World War II, it once served as the building of the Taipei City Hall under the Nationalist government. During the term of Chen Shui-Bian, the first mayor from the opposing political party to be elected in Taipei, the building, deemed a heritage site, became a designated site for promoting contemporary art. The identity transitions of this historical building fully aligned with the changes of Taiwan’s ruling government. Prior to becoming the Museum of Contemporary Art that we are all familiar with today, the sense of “others” associated with it was far more remote than the “others” referred to by Augé. It is difficult to perceive the Japanese colonization of Taiwan or the autocratic rule of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) after it retreated to Taiwan as a collective history, not to mention the sanctity, despite being shattered, still overflows with a sense of collectiveness, which then turned the place into a contemporary art base for us.

Kuo Yu-Ping, For Whom We Flight, mixed media, dimensions variable (Photograph by Huang Ling-Jun, courtesy of Art Square Taiwan)

Approaching Collective History Through Individuality

Perhaps, it is precisely due to this extremely difficult positioning of art that the distance from sanctity seems to be pulling further away, with collectiveness turned into an unreachable coordinate. Consequently, the gaze on the incidents and things next to or near us then had to succumb to become an alternative perspective of the collective. However, this compromised alternative cannot and must not be seen as a replacement, because an alternative indicates an option of privilege, with a sense of self retained – Considering this sense of retainment and privilege, on the one hand, we are able to see, among these alternatives, other options that are almost realistically impossible, and the power wrangling between these two options (the alternatives and the impossibilities) and the resulting gestures of subjectivity then forms a critical point that must be grasped while seeing these artworks. In observing Shattered Sanctity’s contributing young artists, it is discovered that “individuality” is a keyword that is repeatedly mentioned in the wide range of art projects presented at the TAF Innovation Base, such as the adaptation of personal family history into an alternative subjective historical narrative, as seen with Tseng Po-Hao’s Daily Innovation; Kuo Yu-Ping Kuo’s For Whom We Flight; and Chen Fei-Hao’s The Pacific War, Kenkou Shrine and Family Documents in Translation. After conducting extensive field research, these young artists then approached the impossibilities behind the drafting of a collective history through shattered fragments of history that were once forgotten (despite being fragments, they still imply that a collective history did once exist). Nevertheless, during their processes of re-narration, various life stories with close ties to the artists are interspersed throughout but only serve as alternatives.

Chang Li-Ren, Battle City – Scene: School, mixed media, 240 x 240 x 90 cm (Photograph by Huang Ling-Jun, courtesy of Art Square Taiwan)

I find it difficult to find an effective terminology to describe this kind of creative endeavor that is capable of retaining historical fragments while also functioning as an alternative. However, similar attempts of such alternative manipulation, which places individuality in a larger context, have made repeated appearances in the sphere of Taiwanese contemporary art. For example, neoliberalism is insinuated by Kao Jun-Honn through his mother who works at a stall in a traditional market in New Taipei City. Furthermore, Time Splits in the River, 3 a nominee of the 15th Taishin Arts Award, sees the parents of a group of young artists invited to perform as revolutionary activists during Taiwan’s martial law era, with them subsequently turned into alternative characters. On the other hand, The Narrative Structure of Taiwanese Histories by Chang Wen-Hsuan presents a fabricated list of actors and transforms her family story and Taiwan’s process of democratization into a series of boundless and multilayered structures, and in the artist’s statement, the artist points out the Taiwanese contemporary art reference made in this alternative manipulation is done by “borrowing the name” of the artist, Chen Chieh-Jen. (借名 (tsioh- miâ) means “borrowing name” or “in the name of” and is a method practiced by spirit mediums, which the artist adapts as a method to explain Taiwanese histories.)

Chris Shen, Rastrum, CRT monitor, camera, cable (Photograph by Huang Ling-Jun, courtesy of Art Square Taiwan)

Art Projects Focusing on Formal Transformation

Comparatively speaking, similar structural support comprised of processes of field research is also observed in other art projects shown at MoCA Taipei and its nearby spaces; however, generally speaking, the artists in this exhibition have exerted more effort in dealing with how to convert the materials collected. For example, Rastrum by Chris Shen captures images of people moving about both inside and outside of MoCa Taipei, with difficult-to-discern noises then gradually incorporated. Scenery and Mood by Xin Shen and May Heek transforms excerpts of Japanese colonial author Nishikawa Mitsuru’s writing which exoticized Taiwan into a dazzling light-and-shadow installation. On the other hand, this kind of transformation can sometimes transpire into an interactive interface of relational aesthetics, as seen in A Report on a Public Aquarium by Lin Jin-Da. After conducting field research on certain objects and history that are associated with an aquarium in Kaohsiung, the artist then writes a piece, titled The Birthday Party, to present his findings; however, members of the audience are requested to move from MoCA Taipei to a nearby bar in order to read it.

Lin Jin-Da, A Report on a Public Aquarium (Photograph by Huang Ling-Jun, courtesy of Art Square Taiwan)

In seeing these project-based artworks that shift our focus towards formal transformation, it is discovered that the sense of collective history that they evoke is far less prominent than the artworks presented at the TAF Innovation Base, and replacing that sense of history is a poetic gesture, with the line between ideology and action blurred. The histories that were unable to transpire into a collective seem to have retreated and become a kind of perceptual rhythm that dwells in the city. The audience’s viewing or participation may resemble the aforementioned ripples on a lake, with us feeling more inclined to intimately experience these artworks. Perhaps, we need or maybe don’t wish for those illuminations or that bottle of gourd-shaped brandy from 1985 to attain artifactual meaning; however, it is exactly under this ambiguous subjective state with options available that Shattered Sanctity has prompted a feeling that’s quite abstruse, and rather than referring to it as directly confronting that sense of history, the feeling evoked by its disappearance is one that is quite ambiguous. Perceptions toward the “shattered fragments” then become quite prominent in this collection of artworks, and on the other hand, the artworks at the TAF Innovation Base, although given individual positions within the context of history, they, however, do lean more towards the side of “sanctity”.

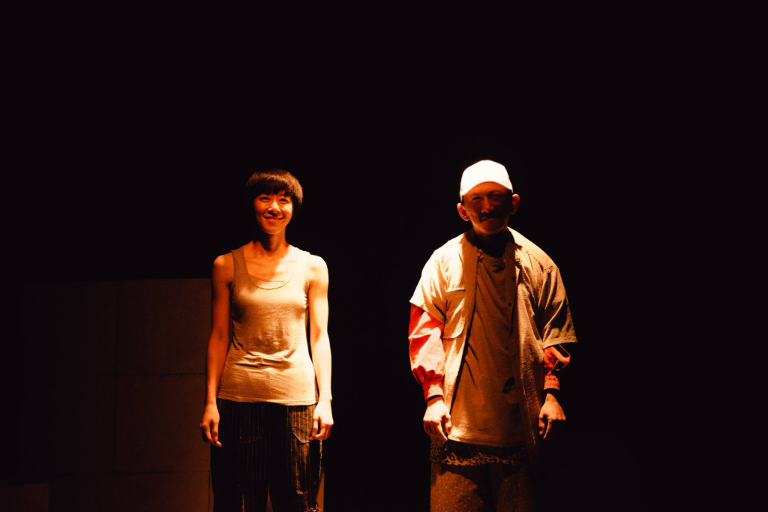

Snow Huang + Against Again Troupe, Here and Other Places (Photograph by Tang Chien-Che, courtesy of Against Again Troupe)

Never-Before-Seen Perceptual Modality

Regardless of their tendencies to lean toward the side of the shattered fragments or sanctity, these artists have propelled us to read, reflect, and then reach beyond the sentimentalities for history, while also pointing at shattered places with dissipating histories. Beyond establishing a relationship model for perceptual activities between their artworks and the local places, I also think that this kind of “relationship model that extends beyond perceptuality” is an account of that thing which exists between the shattered and the sanctified. The problematics raised by the curator, Yi-Hsin Nicole Lai, through her curatorial practice also happened to reflect on the collective consciousness of Taiwan’s contemporary art community: This collective consciousness demands to see this notion of “local place” not only through the perspective of history but also institutionally. Rather than nonchalantly relying on a context that’s dictated by others, through multiple connecting nodes that seem to infinitely extend, attempts are made to reorganize a series of never-before-seen platforms for perceptual sharing. The most moving part about Shattered Sanctity is it shows a persistent effort towards this goal.

The wood shack erected on the square of MoCa Taipei, which displays the life history of the local area and an archive of investigations done by Lai and the artists on the exhibition/performance spaces in Taipei, prompted further thoughts on how an art practice can extend beyond the preconceived context established by others, while also continuing to progress on a path that is not dictated by the industry? Since the curator and the artists have steadfastly made their way into the local community, I think they have already proven the immense possibilities that an art practice could have, and although Lai seems to have chosen one that is quite daunting and unrewarding, it is, nevertheless, a heart-moving cause that seeks to anchor down reality in a sea of infinite alternatives.

The wood shack erected on the square of MoCa Taipei, which displays the life history of the local area and an archive of investigations done by Lai and the artists on the exhibition/performance spaces in Taipei, prompted further thoughts on how an art practice can extend beyond the preconceived context established by others, while also continuing to progress on a path that is not dictated by the industry? Since the curator and the artists have steadfastly made their way into the local community, I think they have already proven the immense possibilities that an art practice could have, and although Lai seems to have chosen one that is quite daunting and unrewarding, it is, nevertheless, a heart-moving cause that seeks to anchor down reality in a sea of infinite alternatives.

Notes

[1] The quotes in this paragraph are excerpts from the brochure provided by MoCA, Taipei for the exhibition, Shattered Sanctity.

[2] This sentence is shown in parentheses in the book, and semantically, a sense of detachment is projected through a tone of tacit sarcasm; Augé, Marc. In the Metro. Translated by Tom Conley, U of Minnesota Press, 2002, p.24,

https://books.google.com.tw/books/about/In_the_Metro.html?id=eq9fcaHyov4C&redir_esc=y.

[3] Time Splits in the River is a collaborative “movie” created by the following four artists, Wang Yu-Ping, Lee Chia-Hung, Huang I-Chieh, and Liao Xuan-Zhen. The screenplay revolves around political activist and literary writer and art painter, Shih Ming-Cheng, with the fathers of the four artists starring in the movie. In order to make this film, the artists had to engage in trans-generational dialogues with their fathers, and those fathers are not professional actors nor were they victims of political violence. Their amateur performance repeatedly diverted the film away from its predetermined narrative and shifted the actors from their portrayed characters back to being fathers.

*Aranslator: Hui-Fen Anna Liao

More CASE STUDY