Su Yu-Ting became interested in writing and doing interviews when she was in high school, and following her interest, she later studied in the Television News Division at the Department of Journalism of National Chengchi University (NCCU). In addition to learning about the production process of television news programs, she also worked as an assistant at the NCCU Audio Video Lab. Deeply influenced by Prof. Kuo Li-Hsin and her other teachers, Su began to study extensively the documentary format’s potential and criticality. Unlike many of her peers who aimed to work at television news stations, after working on some public sector video projects and also at a documentary channel and a cartoon channel, she wanted to break free from the constraints of being an employee and wanted to gain more control over her work. She then began to work as a freelancer and took on production projects from Da Ai Television, the Environmental Protection Administration, the National Science and Technology Council, and Yahoo. However, the efficiency-driven and profit-oriented type of projects made her feel somewhat perplexed and exhausted. Su then saw the documentary, The Man behind the Book, about the literary writer, Wang Wen-Hsing. Wang’s unhurried yet profound work inspired her to write the following wistful words on the first day of 2012:

“I want to be a good communicator, to spread good stories and ideas; I want to be a good documenter, someone who painstakingly documents this epoch.”

In April of the same year, Su met Yang San-Eii, a person who stays outside of conventions and remains true to himself. To fulfill her new year’s wish, she traveled to the small town of Fangliao in southern Taiwan to document this man whom the locals thought was strong-headed and stubborn like a “Woodman.”

Yang’s father was falsely accused in Taiwan’s White Terror Period and was imprisoned at the Tucheng Detention Center. It was a time of extreme poverty, and the seven children in the family all relied on their mother’s work to survive. A year after their father’s detainment, their mother died from exhaustion caused by overwork. Yang San-Eii was only 13 years old at the time. Their neighbors were afraid of getting involved and did not interact with Yang’s family, which led to Yang’s “lone wolf” mentality of doing things on his own. He spent the first half of his life as a vagabond, drifting from one place to another, having little contact with other people in his hometown.

Yang’s “lone wolf” mentality is also apparent in the way he works. “Woody Daddy” (一冊木造技研所) is Yang’s “family business” and specializes in only one type of work, which is to build a family house out of wood using only mortise-and-tenon joints. Yang understands very little Japanese, but referring to the Kanji characters and the illustrations in a book on timber-frame houses by Japanese architect Ikuo Matsui and along with some fundamental skills he had acquired in his younger years working on construction projects, Yang started to draft design plans, sand down wood, and drill and polish wooden joinery, and at this point, he was already on his 8th year of preparation for this house. Su’s original plan was to spend about 5-10 days documenting this story for a television station’s green architecture documentary program; however, Yang was unable to give a clear schedule on when this house would be completed. The circumstances made it unfit for the television program. The master’s demand for his house could not be gauged by the modern way of measuring time, and the documenter had to learn how to apply the same temporal logic in order to understand what was in front of her.

Since it was impossible to turn this story into a television program, Su then decided to make a documentary. She had to wait around and film whenever possible, which required countless trips back and forth down south and up north. Like the rings on a tree trunk that show the accrual of nature’s changes, the footage captured by Su piled up in gigabytes and then terabytes. Yang continued to build the house, and Su continued to document it; however, the one thing that stayed unchanged was the completion date of the house remained unclear.

“Within the scope of the world’s history of architecture, he’s someone who will never be thought of as a Lu Ban-like figure (Lu Ban is the god of carpentry and masonry in Chinese folk religion). In Taiwan, where society pays emphatic attention to a person’s work, education, money, and quick success, Yang appears kind of crazy and foolish. However, with more understanding gained on his dedication, hard work, determination to the craft, and devotion to research and development, which were observed from the discussions he had with artisans of ritual king boats on their waterproofing techniques; his use of oyster-shell ash on walls for better breathability; and him asking an apprentice to send a message via social media to the Japanese wooden-building expert, Ikuo Matsui, to invite Mr. Matsui to Taiwan to give him advice on the house he was building (which a positive reply was received), Yang’s actions seemed so farfetched but also quite exciting and uplifting.”

After Passing Away film-still. After years of anticipation, the beam-erecting ceremony is finally carried out by a religious priest. The beam is lifted using a hoist cable made by Yang San-Eii. (Courtesy of Su Yu-Ting)

However, both Yang and Su were confronted with the same dilemma: Without a sufficient budget, the materials, workers, and machinery required for the construction had to be put on hold; on the other hand, in order to capture high-quality footage, it was imperative for Su to hire a professional camera crew, and considering the conditions of weather and other uncontrollable factors, the money required for making the documentary was quite hefty.

Su applied for as many grants as she could, which included grants from the New Taipei City Documentary Film Awards, CNEX, and the National Culture and Arts Foundation (NCAF), which generated mixed results. In 2013, her short film, Woody Daddy, was selected by the CNEX Annual Theme Project, which marked an interim progress for the documentary on Master Yang’s story. However, the short film format was inadequate in fully recounting Yang’s story, and Su also had to fight hard to obtain the rights to use the footage she had captured and to further develop the film. She learned a great deal about copyright issues from the free legal consultation service offered by the Taipei Documentary Filmmakers’ Union. As a reminder, she urges her colleagues to pay thorough attention to the terms listed in any contracts that they sign, and it would be wise to have an attorney review the terms prior to signing. The different experiences led her to transition from being a simple creator to becoming someone who’s more knowledgeable about film production. She then took on both roles of director and producer in her other documentary series, Happy Birthday and Our Happy Birthday. Although it was a necessary step for her to put on multiple hats due to resource constraints, it also opened up more possibilities for her to think about the needs of film production from different perspectives.

For example, although the Birthday series wasn’t a large-scale production, it, nonetheless, still involved comprehensive steps that included the creative process, project proposals, grant applications, showcases, fundraisings, screenings, and the film release (for further details, please refer to the interview on NCAF’s Audiovisual Media Grants - Research Project: “After Completion – A Study on Taiwanese Documentary Film Release and Marketing Experiences”). The project was also a learning experience for Su, as she observed and made comparisons along the way, and with different references gathered, she then began to contemplate on a better way to tell Master Yang’s story.

“In the short film, Woody Daddy, Master Yang was the focus of the story, which showed this devoted odd man and his determination to uphold this traditional artistry. However, with more time spent with them, I began to grow more familiar with Master Yang’s family, and other storylines then gradually became more apparent.”

“The emotional ties between the members of the family made Yang San-Eii’s story even more special. His wife has always stayed by his side, and despite the occasional complaints and frustration, through communication and acceptance, she continues to support her husband to fulfill his dream.”

Their relationship reminded Su of the film director Ang Lee and his wife: “She didn’t support Ang Lee because of who he had later become. Love is never an investment, and this is also true for Yang San-Eii’s wife.” After realizing that the achievement of the protagonist was made possible through the support of his entire family, the focus of the ensuing filming was consciously also placed on Yang’s wife, daughters, sons-in-law, other family members, and also his apprentices. There was a scene when Yang was working on the rooftop, and his wife had carefully climbed up the shaky wooden ladder just to remind him to be careful. The exchange between them seemed quite ordinary but was full of understated but deep emotions.

After Passing Away film-still. The love that Yang San-Eii’s wife has for him is shown through her daily chatter and nagging. (Courtesy of Su Yu-Ting)

After Passing Away film-still. Yang San-Eii’s wife, Hui-Chuan, is his greatest support and also the most hard-working supervisor. (Courtesy of Su Yu-Ting)

“His wife’s eyes were full of concern, hope, and also various mixed emotions. I really like that particular scene. It shows that a home is not just the work of a single builder but also involves those who are there to extend their support.”

With the schedule of the filming extended, the construction of the house was still unfolding at an unhurried pace; however, the story of the family was changing. Yang’s eldest daughter was originally pursuing a career in sales, hoping to make money to support her father’s dream of building the house, but she had at this time transitioned to work in the theater field as a production stage manager. Her husband then began to take part in Yang’s project, seeking to incorporate ideas and thoughts from the younger generation in order to create more opportunities for the house-building project and to generate some income, including pitching fundraising proposals, social media management, media exposure, etc. Influenced by her father, Yang’s younger daughter, who studied interior design in school, also has her own ideas on what makes an ideal dwelling place and has decided to live, work, and raise her own family in a city. With more in-depth involvement in their everyday life, the bickering and quarrel between the family then naturally became a part of the footage captured.

“I was no longer only pointing my camera at this self-taught house-builder but was focusing on these three women who, throughout more than a decade, have cried and laughed all because of this dream of his.”

Slowly but surely, Woody Daddy then transformed into After Passing Away.

After Passing Away film-still. Yang’s youngest daughter, Ching-Wen, was influenced by his father and now works in the field of interior design. She greatly admires her father’s unique approach to building the house with his own hands but doesn’t think she is capable of taking over. (Courtesy of Su Yu-Ting)

Because of the extended filming period and the process of developing the short film into a feature-length documentary, the budget required skyrocketed. Su had twice applied for NCAF’s documentary grant but was unsuccessful the first time in 2013. She then tried again in 2020 and was selected by the jury committee this time around. When asked about her thoughts on the different outcomes for the two grant proposals she had submitted, she said she wasn’t quite sure about the direction of the film when she submitted her first proposal. She hadn’t spent enough time with the subjects she was filming, and the story, at that time, also focused more on the life of one individual person and the craftsmanship side of house-building. A few years later, she had accumulated enough footage for After Passing Away and was much clearer about the direction of the story. The various developmental trajectories of Yang’s family members were also clearly shown in the film trailer, allowing the audience to better connect with the story. At this point, the film had also reached the post-production stage, and while making the presentation for the grant, Su was much more certain about what she was doing.

The filming and production costs in the first few years were paid for with the income Su was making from other jobs, and when the NCAF grant was approved, a more sufficient budget was allotted for the post-production, which gave her a chance to fulfill some minor dreams she had for the project, including inviting Ken Ohtake, a Japanese musician who has collaborated extensively with some Taiwanese independent bands, to compose the music for the documentary. On the one hand, this decision was made because of Yang’s fondness for the Japanese culture, which he was drawn to due to how the artistry of wooden houses is preserved in Japan. On the other hand, Ken Ohtake’s music was what Su had envisioned After Passing Away would sound like, with the melody of his acoustic guitar used to express the long and repetitive process of building the house, the passing of the seasons, and the family’s delicate emotional connections.

The inspiration behind the lyrics of the documentary’s theme song, also titled After Passing Away, came during the post-production when Su tried to imagine if she were Yang’s mother, what would she say to him knowing that she was about to leave her 13-year-old son behind? Su wanted to write in Taiwanese, which is Yang’s most comfortable language, but she felt that was not very good at it, so she then reached out to Taiwanese songwriter Ong Chiau-Hoa to help with the lyrics. The song aptly captured her thoughts, with the unique rhythmic charm of the Taiwanese language also showcased.

“But this ruthless world, makes living harder than leaving.” This line in the song shows a mother’s tender love for her son, and hopefully, after the long house-building journey, the song can bring some comfort to this man who has spent his entire life searching for a “home.”

The singer who performed the song was another dream come true. Su invited the talented singer Yujun Wang to sing “A Hundred Years Later” and shared the emotions and the story behind the lyrics with Wang. Wang then gave a heartfelt performance of the song at the recording studio, which moved Su to tears, and Ken Ohtake, the composer and guitarist, also exclaimed, “This is it!” After Passing Away was further enriched and made more complete due to the music, the singing, the emotions, the artists’ moving performance, and the recording engineering, which superbly enhanced the documentary.

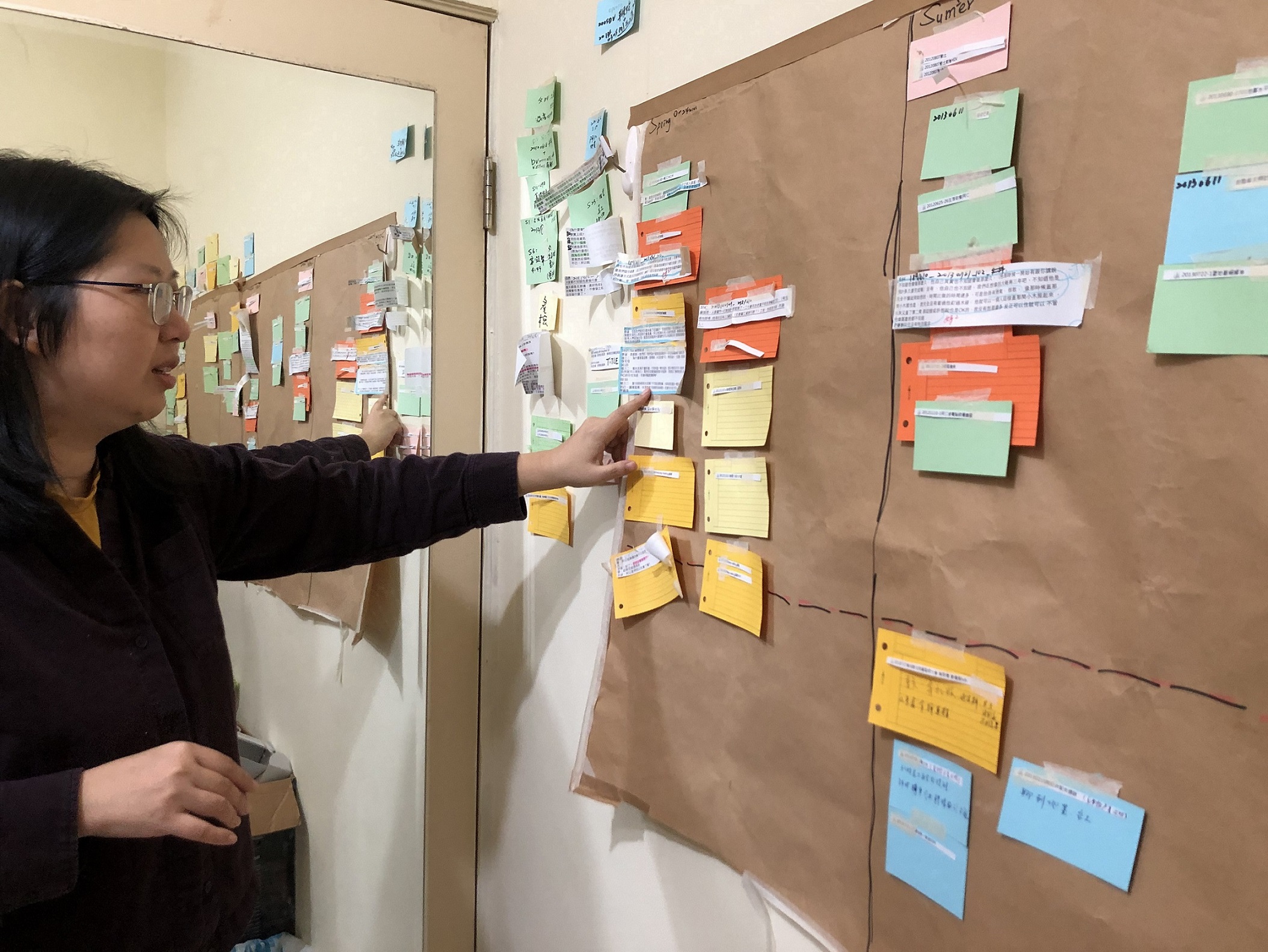

Su is also grateful to the film’s executive producer, Mr. Liao Ching-Sung. She had participated in an editing workshop led by Liao, and because of Liao’s advice and guidance, Su, who was without a clear direction at the time, was able to see a bright beacon of light. She then decided to discard the first three edits that were made and tried to reexamine the chaotic footage she had on hand, and together with a new partner she had working with her, they then restarted the editing process. After the workshop, she also mustered up the courage to ask Liao to continue to mentor her and was surprised to receive a positive response from him. Liao had agreed to act as the film’s producer despite his busy schedule and also accompanied Su and the editor to sort through the footage again and try to feel the message that the footage was conveying. They were asked tirelessly by Liao, “What were you trying to convey when you shot this scene?” The editor, Lin Shi-wan, patiently processed over 150 hours of footage, and they then discussed each scene, one by one, with notes and sketches covering an entire wall. (Su even went out of her way to convert the guest room in her apartment into an editing studio!) They moved around different scenes and made countless edits and adjustments. Together, they then slowly took in and condensed everything to produce a new version of the film.

Su Yu-Ting editing. The countless footage made the editing process quite daunting. (Photo by Chen Yu-Ching)

“Through After Passing Away, we can see the transformation of Taiwanese families after the turn of the millennium,” said Liao.

With Liao’s support, Su was able to feel more confident to steadily continue with the editing, mixing, color correction, and other post-production tasks for the film. The feedback received after several small screenings was also quite positive, and some friends who had seen the previous version also commented that the film felt like it had gone through a great transformation, and they were looking forward to seeing After Passing Away on the big screen and for it to reach a wider audience. Invitations were always sent to film distributors, members of the media, and film critics, hoping they would come to see the film, write reviews, and help distribute or promote the film.

“But people seem to always be so busy, and sometimes things would feel like they were heading in the right direction on the phone, but we wouldn’t hear back from them after the link of the film was sent over to them. Maybe they just have a lot of films to watch, and the documentary is long and not very thrilling or eye-catching,” said Su. She then decided to try submitting to film festivals. In September 2022, great news came her way from the 27th Busan International Film Festival: After Passing Away was nominated for its “Wide Angle Documentary Competition,” which meant an international premiere of the film!

This was Su’s second nomination at the Busan International Film Festival, and her first was for Our Happy Birth Day. This time she was able to attend the event and calmly observe the film festival from the perspective of a film producer. Because of the festival’s large scale and wide selection of films, it was hard to tell if it had a particular preference, and she wondered why After Passing Away was selected that year. From the audience feedback received from the world premiere held at Busan, she then learned, “The subject of ‘home’ is something that everyone cares about, and the story of ‘home’ and ‘house’ can transcend beyond languages and resonate with people.”

A woman in the audience shared that her father was also a carpenter and had built a house for her family. Unfortunately, they were unable to keep the house due to maintenance difficulties. Thinking back to the 10 years she had spent filming the project, the Yang family had to stay in the leaking attic of a restaurant or in a makeshift tent at the construction site, as they waited for their father to build the house. They had minimized their material desires, overcome challenges in life, and even put up with gossipy neighbors. After countless mistakes and do-overs, the dream house finally came true. “Failure is normal, but this success is well deserved,” said Yang. The director couldn't help but get choked up when she was responding to this audience member. Su also noted that the viewers in Korea were quite enthusiastic, and some even came up to her outside of the theater after the screening to ask for her autograph and photos and to ask for more information about the film. The feedback received was greatly encouraging to Su, and it was truly rewarding to see the audience enjoying and expressing interest in her work.

For this story from a small rural town in Fangliao, Taiwan to resonate with an international audience, this was a diplomatic exchange that required no use of fancy words.

After they returned to Taiwan, After Passing Away was shortly selected for the Kaohsiung Film Festival and was the top audience-choice film that week. Director Kuo Liang-Yin once said, “The audience-choice award is the best award to receive for a director!” And indeed, it was.

To be screened in film festivals allows a documentary to gain more exposure, but there are many different film festivals in the world, and which film festival to submit to and when, where to host the screening, how the promotion should be executed, and how to compete for awards, these details won’t just take care of themselves simply because of how heart-moving a film is. Su is still learning about these different aspects. Taking on both roles as the director and producer, the things that she needs to consider often contradict one another, and tasks need to be delegated between the director and producer.

“Ideally, a producer should start to work with the team in the planning stage and begin to seek out resources at that point; otherwise, in the post-production stage, it becomes very difficult to edit and look for resources at the same time. With limited time and energy, it is impossible to consider the different factors involved at that point; it becomes much more challenging.”

Is it possible to secure the resources needed at the planning stage? Based on Su’s observations of most film distributors, they tend to take an observational stance when it comes to new directors and new projects, and it’s rare to get their attention at the planning or preliminary editing stages of a film. However, at the later stage of editing and toward the trial screening stage, any changes made would likely increase the project’s cost by a lot. At this point, without the needed funding and the time to make changes, film festivals then become the only possibility available, and if lucky and your film is chosen, the distributors would then be more willing to negotiate. However, the filmmaker is working alone in this process and is mostly betting on luck, but this way of doing things shouldn’t be the norm.

Using the documentary, A Holy Family, as an example, Su explained that the filmmaker of this documentary had entered into a 12-year contract with the production team, which turned the relationship into a collaborative partnership, and additionally, with international financial support that was initially secured, they were able to raise the pre-production standards for the film and to seek out more resources for further development, which allowed for better filming and post-production processes, which then opened up more opportunities for the film to be selected by film festivals and more sales income made from international royalty.

As a busy mother who was also juggling the post-production work of After Passing Away and other freelance jobs, Su somehow managed to muster up more energy to initiate an event series where entrepreneurial and innovative endeavors were shared. This 5-part event was called the “Ark Project” and took place between March and July 2021, and during the meetings, vegetarian food was offered, with entrepreneurial and innovative experiences shared, and old and new friends freely interacted with each other (there were even prize draws!) The speakers invited to the event were not limited to documentary filmmakers and also included website designers, poets, entrepreneurs, social activists, etc.

As described by Su, “Each content creator has a dream, which is to have their creative works be seen by more people. In this era of excessive audio-visual content, we sincerely invite you to come and share your entrepreneurial, creative, interactive, or fundraising projects, and let’s join together to work hard and take our creative works to reach further…We won’t be talking about how to get into the Taipei Golden Horse Film Festival, venture capitals, or editing techniques. We will focus on creative work, talk about life, and discuss what you usually don’t want others to see, which is what really happens behind the scenes.”

Su was asked by some friends whether she was overburdened by the editing process and was wishing to hop on an ark to escape from the overwhelming flood-like footage in front of her. What sort of sparks would ignite when cynical social activists cross paths with yuppie venture capitalists? Would successful elements of social activism and venture capitalism be noticed through the sharing of such experiences? Hopefully, this ark would continue to sail forward and nurture new breeds of talents.

It is inevitable to be confronted with different “people” issues when making a documentary, and without an understanding of how to deal with people, it would be difficult to probe deep into the inner world of the film’s subjects and to gain their trust, and it would also be hard for the filmmaker to realize what they are seeking to respond to by making the documentary. After Passing Away is no exception. Without Yang’s extraordinary determination and stubbornness, it would be impossible for him to continue to build this house for 18 years. However, when facing his own family, his stubbornness is also sometimes hurtful. The documentary ends on a gentle note with Yang lovingly looking at a new member of his family. New life is added to the family’s story, and it continues to evolve.

With the post-production completed and the documentary openly screened, the natural progression for any documentary at this point should involve expanded social outreach, with the ideas and philosophies of the filmmaker and the subjects documented shared with as many people as possible. However, life is often not quite so predictable. This wooden house and the legendary tale of its construction were covered by both the print media and online news outlets which turned it into a hot destination in Southern Taiwan, and it sparked various imaginative thoughts and expectations from various people in society. Having endured an extended period of hardship, the family’s house was finally finished, but they were also confronted with new problems. Some of the issues that unfolded in reality took place beyond the camera and did not make it into the film, so was only the good side shown to the audience?

After Passing Away film-still. Yang’s eldest daughter, Chi-Shu, uses cultural and creative-oriented tactics to pitch proposals to help her father Yang San-Eii realize his dream. (Courtesy of Su Yu-ting)

Su explained that the interaction with the subjects being filmed when making a documentary is a long and extended process. It is integral for the director to remain true to their creative vision and to also respect the subjects’ willingness to be filmed. The signing of a “Filming Consent Agreement” is demanded by some documentary commissioners, which would confirm the subjects’ willingness to be filmed. It is also recommended by lawyers that the consent form should be signed at the initial stage of filming. However, Su mentioned that even with a consent agreement signed in the beginning, if a subject has a change of heart during the filming, it would still be impossible for the director to force the subject to follow the terms listed in the agreement. A documentary is a real story, an extension of life, and even with a legal agreement signed, it still doesn’t mean that everything will happen accordingly. In order for the subjects being filmed to accept the filmmaker, the process involves more than just a singular point of view, and it is also not about which side to take; more importantly, a documentary is not a tool; it requires thorough and trustworthy communication.

What about when an audience disagrees with the filmmaker’s perspective? Su believes that it is impossible to have everyone in the audience to share your point of view. Creative work is not a service that aims to please everyone.

The making of After Passing Away originated from her own anxieties about finding a dwelling place for the family she has made in the city. After seeing different types of houses, she then met Master Yang by chance, which then opened up this visual document about the Taiwanese people and the notion of “home,” which shows people’s obsession with home, a story of a family’s bond, and also many open imaginative thoughts about what makes a place home.

A big tree grabs tightly onto the land with its complex roots, as it aims to stand tall and thrive. After Passing Away is also about a unique and complex ongoing story that is deeply rooted in this land. In the words of Yang San-Eii’s eldest son-in-law, Yu-Chien, “Home is a forever ongoing project.” As a filmmaker who had accompanied the family on a part of their journey, Su said with great sentiment, “Images are highly illusive, but they can also realistically present people’s lives. I have the ability to express and communicate. If this ability is used for the pursuit of money and fame, I will never feel content. If it is used for the preservation of what’s kind and good, to defend against evil, and to seek the truth, the passion within me will continue to burn and fill my spirit with great strength.”

*Translator: Hui-Fen Anna Liao

More CASE STUDY