The Complicated Fixation with the Quest for the Father in Post-Martial Law Taiwanese Narrative

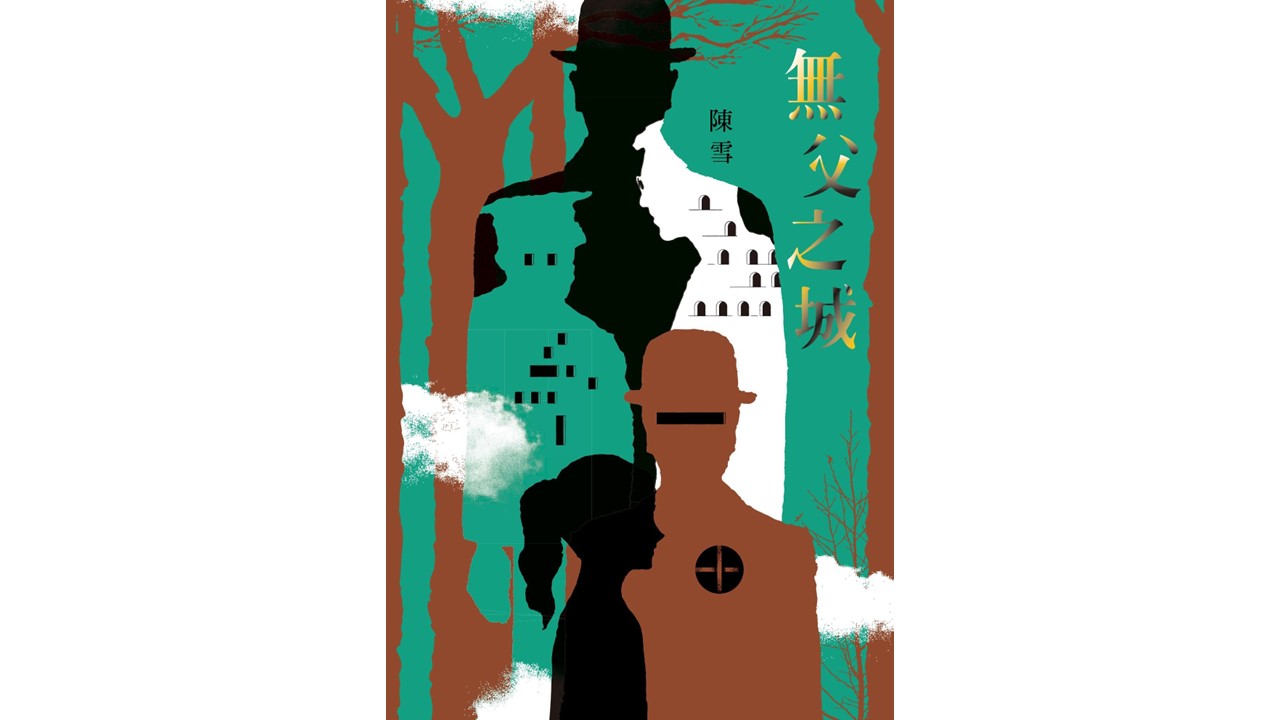

The literary scene is becoming more and more complex in Taiwan with each passing day. It seems difficult to imagine that in 1987, when Martial Law was finally lifted, society in Taiwan would develop in the way that it has, moving farther and farther away from mainland China, in part due to the different political and social situations, but at the same time still feeling the effects of some age-old themes in Chinese cultural and literary history. Contemporary Taiwan has moved forward in unprecedented ways to work toward securing the rights of the LGBTQ community in ways that very few states in Asia have. Taiwan is setting the tone for tolerance of Gay Rights for the rest of Asia and for other places in the world. The contemporary author Chen Xue (陳雪) is one of the most vibrant and creative voices in the LGBTQ movement. Her work has been pathbreaking and has opened up a space in which others feel safe to speak. Her novel Fatherless City (無父之城, 2019) is a complicated, sophisticated, and fascinating intervention into the world in which conventional familial and kinship relationships can be reconsidered or, more precisely, reimagined. Her work also intersects with some themes, such as filial piety and the search for the father, that have existed in Chinese writing since at least the Ming dynasty and perhaps even longer.

In this essay, I set out to place Chen Xue's novel in the larger context of Chinese/Sinophone narrative, illustrating how the search for the father and the anxiety over the absent father is a recurring theme in Chinese literature dating at least to the Ming dynasty. The intertextual links between Chen Xue's work and earlier works not only help us better understand her work, they also enable us to see some of the truly creative aspects of her own novel. Among the most important themes in Chinese literature, philosophy, and historical writing is that of filiality: the powerful connection between fathers and sons in Chinese society but also the governing discursive logic that legitimates the patriarchal social structure, networks of kinship, and a system of belief that privileges the bond between humans in the terrestrial world and ancestors in the celestial realm. The powerful historical context of filiality tends to haunt even the most radical works of fiction in the contemporary Sinosphere, both within mainland China and outside its borders. Also haunting this particular work, and distinguishing it from works from mainland China per se, is the legacy of the White Terror in Taiwan that raged from the late 1940s until the mid-1980s. The White Terror, extrajudicial executions and imprisonments, authoritarian rule, and the fear engendered by martial law together conspire to contaminate virtually all aspects of Taiwanese society and all relationships. Its effects can be seen in many literary works, such as those of Chen Yingzhen (陳映真) and others, and cinematic representations, such as those of Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢) and Yang Dechang (楊德昌). Fatherless City joins in this collective ritual remembering of the White Terror period and displays the way in which its tentacles dig into and latch themselves onto the consciousness of Taiwanese people even long after the lifting of Martial Law in 1987.

In Fatherless City, as Carlos Rojas has summarized in the only English-language study of the novel that I know of, Wang Menglan, the female protagonist, seeks refuge from the stresses of urban Taipei and from her own anxious feelings stemming from writer's block. While there, she engages in several assignments wherein she essentially ghost-writes or attempts to ghost-write the stories of other people, a practice that proves liberating and enlightening for her. Among these narratives there is one that she creates for a man named Lin Yongfeng who would like an imagined narrative to be attached to the prison years his father endured during the White Terror. In the process of creating a fictional account of Lin's father's years of detention, Wang Menglan's feelings toward her own father and the consciousness of his suicide infiltrate her thoughts. She later discovers that the presumptions on which she based her fictional account of Lin's father's life were completely false, a point I will return to at the end of this essay. For now, it is important to note that in Chinese narrative there is no easy escape from the bonds of intergenerational relations, perhaps a universal fact but certainly one that is accentuated in Chinese and East Asian societies. Examining some of the other texts in which the search for the father dominate the narrative will help to contextualize Chen Xue's novel.

Fatherless City (無父之城) by Chen Xue.

Late Imperial Narratives of Filial Quest and the Story of Wang Yuan

Tales of filial exemplars populate traditional Chinese narrative of all eras in abundant numbers. What we do not see, according to Maria Franca Sibau, is instances of the filial quest (尋父故事, also known as 萬里尋親): stories where a son scours the countryside for his father. This changes with two vernacular stories of Wang Yuan entitled "Fleeing from the Local Tyrant the Coward Runs Far Away, Through a Premonitory Dream the Filial Son Meets His Parent" (避豪惡懦夫遠竄, 感夢兆孝子逢親) and "Wang Benli Searches for His Father at the Far End of the Empire" (王本立天涯求父). The first appears in Exemplary Words for the World (型世言, published in 1645); the second is collected in Rocks Not Their Heads (石點頭, c. 1627). Although these two narratives of Wang Yuan's story share the basic plot and many of the details, crucially, the overall emphasis of each story is radically different from the other. There are several extraordinary features that the stories share. For example, Wang Yuan or Wang Benli, as he is familiarly known, drops everything including his own wife and child to go to the ends of the earth to find his father. He eventually finds his father, who it turns out is an irresponsible lout. The father abandoned his son. When Wang Yuan finds him, he is met with hostility and indifference from the father. The father refuses to return home with Wang Yuan. But the point is not that the father is a decent man, that there was some kind of misunderstanding, or that things can be patched together. The father will not acquiesce and follow the son home willingly. The point is that no matter how contemptible the father is, no matter how unworthy of love and respect he seems, the son is compelled to restore and maintain the relationship. The filial relationship is not transactional. It is not an earned right on the part of the father. It is implicitly as solid as adamantine. Sibau suggests that this peculiar level of obeisance to the father is not simply the necessary extension of Confucian values. It is particularly pronounced in works of the late imperial era. In the Exemplary Words for the World version, incredible detail is devoted to all the ways in which Wang Yuan methodically searches for the father and his determination to continue on his journey unabated until the father is found. The two stories make for fascinating yarns and detailed excursions through the human geography of late Imperial China. This elaborate description sets the stage for a modern work, Wang Wenxing's classic novel of the breakdown in filiality and the intergenerational bond, Family Catastrophe (家變, 1971).

The Radical Critique of Filiality and the Redemptive Impulse

Wang Wenxing's (王文興) novel Family Catastrophe (家變) has largely been read as an extension to the May Fourth critique of patriarchy, an evisceration of the poisoned father-son kinship relationship as it was depicted in the early 20th century. What is often overlooked, except in the article that I wrote, is that a significant amount of the narrative focuses on the search for the father after he has fled the home, a search that takes place in the narrative present. This narrative is organized from A to O. Like the Ming tale of Wang Yuan, there is an obsessive quality to the search for the father and a complete elision of all the conflicts and differences between father and son. Those intergenerational antagonisms that highlight the fiction of such May Fourth Era writers as Ba Jin (巴金) are simply all pushed aside in the enterprise to find the father and restore the family to its original and proper form.

But this is only a portion of Family Catastrophe, and the most overlooked aspect of the novel at that. Interspersed in between the lettered sections is the narrative of the history of the father and son relationship beginning when the protagonist Fan Ye (范曄) is very young and just beginning to read. This narrative is organized by number, is narrated in the past tense, and charts the devolution of the relationship and disintegration of the family. Together, the two sections constitute competing narrative and moral tones, with one hostile and the other redemptive. When considered as part of a single overall novel, the conclusion the reader can draw is that there is a profound ambivalence with regard to filiality.

The narrative structure of Family Catastrophe is like no other book: it is radical and calls into question the conventional structure of narrative itself. But if we search beneath the structural fact of the interspersed bifurcated narrative per se and ask the question of why would Wang Wenxing structure the narrative in this manner, the true import of the novel is unveiled to us: Wang wanted us to think of the two drives—the drive to oust the father, the conflict, the anti-filial passion on the one hand, and the redemptive urge, the compulsion to restore the family, the contrite, filial sentiment on the other—as being commingled. They are intertwined. They are two sides of the same coin. The novel is, in short, an internal contestation, a narrative at war with itself. Considered in this light, Family Catastrophe is not merely a novel that attacks the moral notion of filiality; it is a novel that equally valorizes filiality as an indispensable ethic, a constitutive element of the Chinese psyche itself. The two conflicting sentiments are enmeshed and not easily torn asunder. Thus, the upshot is that Wang Wenxing's novel illustrates that no matter how radical the critique of filiality is, there is no real getting rid of filiality. This point helps us make sense of Chen Xue's novel.

Luo Yijun's Father-Son-Father Quandary

Luo Yijun's (駱以軍) novel Far Away (遠方) appears as though it could be a semi-autobiographical novel that depicts the first-person narrator as someone caught between the two conflicting poles of kinship obligation: on the one hand, being a filial son and, on the other hand, being a responsible parent and partner to his wife. The novel narrates a situation in which the narrator has just taken his wife, at a very advanced stage of pregnancy, and young son on a vacation to Hualian. He was not there very long when they received a call from his wife’s sister that his father, on a trip to mainland China, had had a stroke. The narrator and his mother had to drop everything and rush to Jiujiang (九江) in Mainland China to see after the father. Much of the frustration and conflict of the novel revolves around the corrupt bureaucracy in mainland China, both on the governmental level and in the hospital where his father was being treated. The main problem was that the government would not issue a travel permit that would enable the father to return to Taiwan. The experiences in the novel—dealing with the doctors and hospital bureaucrats, dealing with the government, thinking about his strained relationship with his father, and thinking about his own young family—cause the first-person narrator to contemplate his place in the world, the meaning of his life, and the necessary fulfillment of obligations that he constantly confronts. The novel depicts a modern situation that is quite plausible, but within the modern condition of two separate governments and political systems at two different stages of economic development, as well as the demands of modern economics that, for instance, foster a desire in many people to reduce the size of the family, to nuclearize, the novel provides a format in which the reader can revisit the classic theme of filiality.

How does filiality work in the specific, material conditions of contemporary China and Taiwan, with many cultural differences between the two societies owing to totally separate historical trajectories over a seventy-year period? How does one deal with being caught between two very different generations—the older one represented by the father, who was still very strict, raised his son using traditional punitive methods, and was not a warm and loving father; the younger one represented by his pregnant wife and their toddler son? He has pressures from both ends. In a spiritual way, the novel could be related to Chen Xue's work. Although the father was physically present in the narrator's life while he was growing up, he was not emotionally available. In other words, it still was a bit like not having a father at all. At the same time, toward the end of the novel the narrator shutters to imagine what life would be like with his father gone, when, albeit at a later age, the narrator would "become an orphan." Another complicating factor of the impact of the sociopolitical situation on the narrator and his family is the fact that in mainland China he has a half-brother who was the offspring of his father and his first wife. This actually was a common phenomenon in Cold War era Taiwan, and it also was a factor in Wang Wenxing's novel. What does this mean for kinship? This is a complicating element of the story.

Far Away (遠方) by Lou Yijun.

The Fixation on Intergenerational Relations and the Redemptive Urge

Undoubtedly, in all societies intergenerational relations are important. Their centrality, socially speaking, is reflected in the literature of societies all over the world. However, in the Chinese society specifically and East Asian societies more generally, intergenerational relations are particularly important. The literary examples discussed in this brief essay represent a range of narratives that deal with the obsession over the father figure and the fear and anxiety over the loss of the father. Interestingly, each one of the novels discussed above is inflected with its own specific historical circumstances. These circumstances add to the tapestry of the description of human relationships. The historical circumstances are not totally determinative of the way in which these relationships are structured or the way they unfold; however, in every case the historical circumstances complicate these relationships.

Returning to Chen Xue's unusual novel, we can see that the stress placed on the protagonist Wang Menglan due to the traumatic loss of her father has led to the development of several different narrative strands. Works like Wang Wenxing's innovative novel Family Catastrophe paved the way for further innovation exhibited in later novels such as Fatherless City. Wang Menglan, Chen Xue's fictional heroine, is herself a writer. Her initial impetus to move to the village of Haishan (海山鎮), where most of the action occurs, was to assist in the writing of the biography of an elderly artist. But the artist dies not long after her arrival, closing that chapter of the story. Coincidentally, a new opportunity arises as a local resident asks her to write the history of his father. As I said near the beginning of this essay, Chen Xue's fictional reconstruction of the biography of Lin Yongfeng's father, a political dissident, did not uncover the real reason for his imprisonment. Writing has a way both of revealing and concealing, frequently at the same time. What is narrative if not the assembly of a number of individual facts and incidents arranged in such a way as to tell a story. The way they are assembled and the fact that sometimes crucial details are left out or diminished while others are accentuated together contribute to the fashioning of the story, which can be contrary to the truth. In fact, the persuasiveness of the story often has more to do with its rhetorical quality than to its adherence to reality. In Chen Xue's book, the protagonist Wang Menglan begins to view herself and her own family differently while in the process of helping write the narratives of other people and their families. As this happens, she also regains her ability to write her own work. In her experiences in the seaside town of Haishan, Wang Menglan not only rewrites the story of Lin Yongfeng's father, she also helps solve the mystery of a young woman, a daughter, who has been murdered. These stories, plus the dismissed plan to write the artist's biography, are what eventually bring Wang Menglan back around to her own story and her own confrontation with the presence of her father in her consciousness. Like many Chinese narratives, no matter how radical the structure and how subversive the subject matter, in the end there is an attempt at redemption. As Carlos Rojas has emphasized, at the end of the novel tears come to the eyes of Wang Menglan, tears not of sadness but of cleansing and absolution. Wang Menglan leaves the reader at the conclusion of the novel with a feeling of redemption, that she has come to terms with the loss of her father and that she has learned to accept it. Chen Xue teaches us that narrative can be a means of confronting the terrible things in our lives, working through them, and developing the ability to accept them and move on.

*About Christopher Lupke

Christopher Lupke (Ph. D. Cornell University) is Professor of Chinese Cultural Studies at the University of Alberta. A scholar of modern and contemporary Chinese literature and cinema, his books include The Sinophone Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien: Culture, Style, Voice, and Motion and a translation of Ye Shitao's monumental work, A History of Taiwan Literature, which one the Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for the translation of a scholarly book from the Modern Language Association. Lupke’s current research project is a book-length study of the Confucian notion of “filiality” in contemporary Chinese and Sinophone fiction.

More OUTLOOK