International exchange has been an emphasis in the grant structure of the National Culture and Arts Foundation (NCAF), both in schemes of regular grants and specific project grants. The transformation of the former project grant, “Pursuit of Excellence in Performing Arts Project” (launched in 2003) into “Performing Arts Abroad Project” in 2015 demonstrates a further step into this. As a strategic response to the development in the field of arts and culture, the NCAF sees international development as a core factor for team growth and artistic advancement. Regular grants are intended for smaller amounts of subsidies which are accessible to more groups regularly for their respective needs. Project grants, designed for specific agenda, provides targeted programs with larger amount of support, often long-term. How do performing arts groups develop their own specific collaboration program with international partners? What impact do these different approaches have on each team? The seven groups interviewed (Formosa Circus Art, Century Contemporary Dance Company, B.DANCE, Body Phase Studio, Our Theatre, Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group, and HORSE) have each opted for a unique way in international exchange. Their experiences is also a reflection of the ecosystem and the future prospect of performing arts groups in Taiwan.

Creating Understanding through Long-term Two-way Pursuit

Before the project-based grant encouraging longer-term exchange was implemented, the Century Contemporary Dance Company (CCDC) has already launched an unofficial exchange platform, “Dance in Asia”, and since 2011, they have co-organized several smaller-scale art festivals with artists in Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong. Different from the conventional pattern of being invited to perform or going on a tour, the approach facilitates exchanges of dancers or production design teams to engage in more in-depth collaborations, with the outcomes performed in different cities that are a part of this collaborative network. The endeavor has been ongoing for over eight years and has expanded in 2018 with the inclusion of partners from Indonesia and Malaysia.

Timeless organized by the Century Contemporary Dance Company in 2016 was a part of its “Dance in Asia” cross-regional project that linked together the Asian cities of Taipei, Tokyo, and Seoul.

The project originated from the community art festival, “Flashmob to Yongkang Street”, organized by the dance company as a platform to present works from young dancers. Yanaihara Mikuni, director of the Japanese dance company off-Nibroll, was quite impressed with the energy exuded by those young artists, and having met CCDC director Yao Shu-Fen years ago at the Asian Performing Arts Festival in Tokyo, the two decided to launch this platform, despite not having secured steady funding for the project. Their objective was to provide opportunities for young artists to collaborate with other artists in Asia and to become familiar with the cultural settings in other countries. Although the productions were not large in scale, they linked together the art communities and the local audiences interested in artistic experiments in each participating city.

The collaborators in each city play a critical role; they not only have to possess the capacity for ways of thinking in contemporary art but also have to be able to handle the logistic aspects of the production in their respective city. For example, if it wasn’t for off-Nibroll’s connections across different fields, it would have been quite impossible to find a venue in the space-scarce and expensive city of Tokyo. For the iteration carried out in Surakarta, Indonesia this year, the local coordinator Melati Suryodarmo was also crucial in securing an independent space located in a jungle, with discussions on Asian traditions and the history of dance highlighted in the project. With opportunities to learn about each other’s environments, including the contemporary art ecosystem, cultural traditions, training and people, the artists in each city are able to organically think about and explore the possibilities associated with the so-called Asian body. It is also one of Yao Shu-Fen’s hopes that an Asian creative network can be steadily developed by the project’s contributors.

“Dance in Asia” is also a reflective response towards large-scale festivals. “If institutional festivals continue to only allow a select few groups to participate in them each year, is the country fittingly represented? I don’t think so, because the development taking place in each country is much more diverse,” says Yao. Due to limited funding, the scale and arrangement need to be adjusted accordingly each time (with the exceptions of Taiwan and Japan, collaborators in other countries do not receive institutional subsidies to support their endeavors). The approach of having experienced artists to guide the emerging talents is preferably employed for any type of arrangements presented, be it a solo dance or a group performance. This allows for the veteran and the young to jointly present their work, and the intention is to encourage the latter to accumulate more experiences year by year. Yao further explains, “Everybody has to start somewhere, which would then benefit them in broadening their horizons. One by one, we will try to guide as many people as possible.”

The dance body itself may transcend language barriers, but verbal communication is nevertheless essential for a more in-depth exchange. That had been a challenge for “Dance in Asia”, as the limited funds could not afford to hire translators. Language barrier is a challenge one must face deal with in theater-related international exchanges. Yukio Nitta, producer of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group (SWSG) believes, “The groups have to get to know each other and be willing to communicate using different languages.” Director of the group, Wang Chia-Ming, sees this advice as a creative stimulation, and before the launch of the grant, “Performing Arts Abroad Project”, Yukio Nitta had already begun to think about different co-production models to introduce the group to Japan. To get to know each other, culturally, is not something that can be rushed, and an equal playing field for both sides is essential when engaging in co-production. Bearing this in mind, SWSG then decided to forgo commissioning well-known big names and opted for group-to-group interaction, with funding equally shared by the participating parties in Taiwan and Japan.

After about four to five years of observation and communication, Yukio Nitta was able to develop partnerships with the Japanese theater company, Dainanagekijo, and the Mie Prefecture Fine Arts Center (Narumi Kouhei works as a resident director for both). By working directly with a local venue, potential problems that may arise when Taiwan engages in international state-to-state exchanges can be avoided, and it was also possible to obtain a multi-year financial support. Subsequently, the launch of the “Performing Arts Abroad Project” came at a fitting time, and SWSG was able to launch its three-year international exchange project, “Notes Exchanges”. Yukio Nitta asserts, “Having spent three years to learn about each other has resulted in a sense of responsibility. We have a sense of responsibility towards the other party.” The period of three years spent working with each other has deepened a sense of tacit understanding between the two collaborators, and now, translation is sometimes unnecessary for them to understand each other.

Café Lumière was presented in 2018 on the 3rd year of the 3-year Taiwan and Japan collaboration project, “Notes Exchange - Dostoevsky, co-initiated by the Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group and Japan’s Dainanagekijo and the Mie Prefecture Fine Arts Center. (Photo by Matsubara Yutaka)

Notably, SWSG did not opt for the model to gradually develop one production during this extended period of exchange; instead, the objective was to try to push for both groups to jointly come up with a new co-production each year. They started with exchanging a single performer in the first year, and in the subsequent years, a director was added or more performers, leading to a more comprehensive and profound partnership, working with the entire production or design teams. “Audience engagement is also essential, which is why we opted to present a production every year,” says Yukio Nitta. After three years of regular performances, the audiences on both sides have taken on a distinct impression for these theater groups from Taiwan and Japan (SWSG has received audience feedback stating that they have noted Wang Chia-Ming seems to be showing influences by Narumi Kouhei’s calm and serene style). Departing from this groundwork, the two parties continue to collaborate with other venues and institutions in both countries, including the Cloud Gate Theater, the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, and the Tokyo Festival, creating more touring possibilities added.

The subject choices and the changes made throughout this three-year co-production project show contextual connections to the local areas. They chose to debut with Dostoevsky in the first year, with a piece created by each of the two directors based on this theme. The second year saw the two directors working collectively, with George Orwell’s novel, 1984, adapted to present their views on contemporary Taiwanese and Japanese societies. The iteration in the third year paid homage to Mie Prefecture native, Ozu Yasujiro, and revisited the history of war in both Taiwan and Japan. The production was an experience that sought to engage in a local dialogue through artistic cultural exchange. “I had to reflect again on how to convert those so-called field research into writing,” says Director Wang Chia-Ming. Wang often employs multiple languages in his creative work, and in the latter two productions, he also used formats such as translation and the separation of the performing voice and the body to further engage in international contextual exploration.

In addition to the productions, both parties also met up annually for approximately a month to do intensive onsite rehearsals and workshops, which also allowed both sides to learn about each other’s everyday cultural customs. The Mie Prefecture Fine Arts Center pays great attention to making local connections and is quite open to creative ideas. It permitted its backstage to be turned into a residency space. The space for rehearsals then became equipped with accommodation facilities, with social activities also made possible there. Such arrangement allowed the groups to get closer to local issues. At the same time, members from Taiwan also had opportunities to interact with the residents in a casual, everyday manner (such as cooking together or hosting cultural workshops). The activities led to closer ties with the public in the Mie Prefecture. Unfortunately, this touring model was unable to be carried out in Taiwan due to the unavailability of a venue that could function as the project’s base. Moreover, because of the industry conditions faced by the Taiwanese performers, it was impossible to work with the same group of people for the project’s three-year duration, which was quite a pity.

SWSG made the conscious decision to propose an international co-production model that differed from the approach of working under “a well-known big name”. However, Our Theatre consciously chose to collaborate with an influential figure to open up a two-way exchange. In 2016, Our Theatre co-produced Paint it Black! with Ryûzanji Sho, who is dubbed Japan’s “King of Experimental Theater”. Although the production was quite large in scale, with over 20 performers and also live musicians, Our Theatre willingly accepted the challenge. The two sides felt an instant connection over their shared aesthetics; however, “our production capabilities were drastically different,” says Our Theatre director, Wang Jhao-Cian. This included the performers’ professional abilities; the assistant director Yamasaki Rieko’s ways of handling the production and rehearsal schedule; or how to compose the sequence of steps and moves, the music, and basically, the operations involved with each department. Our Theatre then proposed to work under a parallel group model, with designers from Taiwan arranged to work as assistants under the various departments in the Japanese company, where they were able to learn and gain insights on things that are hard to come by in Taiwan and also their production methods that integrated music and dance. “We took up three rehearsal rooms at the Chiayi Performing Arts Center each day, where singing lessons, rehearsals, and other practices took place. It was quite a fulfilling experience, and it was something that’s rare to come by once people start to work in the real world,” explains Wang. In the first year of the collaboration, Our Theatre saw this approach of “working under a well-known big name” as an opportunity to comprehensively train and empower its group members. Pain it Black! was Our Theatre’s first work of tragedy, and it propelled their long-term advocacy for classic Taiwanese performances to the next phase.

Paint it Black! was co-produced in 2016 by Our Theatre and Japanese director Ryûzanji Sho.

Our Theater’s exchange program didn’t just stop there. After a failed attempt at securing a grant, the group made another proposal under the title of “Five-Year Bridge-Building”, which progressively turned the two-way interaction into a tangible prospect, and this objective of building a steady development was able to benefit from a grant provided by NCAF, which allowed the group to be able to “take a breather”. The first year was considered a learning stage, with Our Theatre oriented around the Japanese group; however, extending from Our Theatre’s long-term dedication and experiences, the only term they had requested for was to use the Taiwanese language. The request to use the Taiwanese language was not easy for Ryûzanji Sho, whose work highlights the connections between the body and musicality, but he is someone who likes to be challenged. Subsequently, a tour was arranged in Taiwan and Romania. In the third year, a request was made to shift the focus back to the East or even Taiwan, which led to last year’s production, An Oxcart for Dowry. Wang believes that because of the time spent in the previous two years, with this production, Ryûzanji was able to gain better control over the distinctive expressions of the body when using the Taiwanese language and to differentiate it from the Japanese language. At the same time, Wang had to travel to Japan to direct the production performed by the Japanese group, which was followed by a tour. With the duration of 5 years considered a segment for achieving insightful two-way progress, the approach saw Our Theatre gradually shifting from developing standalone productions to becoming a theater group with an operational structure, with the group making efforts to become active in other Asian countries.

“The notion of the ‘ferryman’ proposed by Dr. Wu Jing-Jyi or the concept of a ‘cultural governor’ mentioned by Lu Ming-Shi at the Grasstraw Festival which we organized have all deeply impacted me,” says Wang. A ferryman links together two sides, and it is crucial for the both sides to continue to learn and to make international ties, while also finding that bond with one’s own culture. The experience of observing different cultures together with Ryûzanji Sho inspired the group’s comprehensive planning for the training of its members and also for cultural learning. As suggested by the name of this three-year exchange program, “Direct Delivery from Tokyo, Made in Chiayi: Asian Theater Experimental Base Implementation Project – 1st Phase”, international exchange is regarded by Our Theatre as a driving force behind building their own foundation.

Expanding Dialogue Partners with Knowledge Interchange

A bridge is not only needed when seeking to profoundly understand other cultures, and it is also essential for understanding the traditions of specific performance genres and market expectations. Formosa Circus Art (FOCA) is an example of such a framework. The training of acrobatics in Taiwan has remained structurally confined to the tradition from China, which tends to focus on technical expertise and is rather distant from the concerns and dramautrgies of contemporary circus art. Since its founding in 2013, FOCA has always aimed to find new creative approaches to integratetheir skills. FOCA tours regularly overseas, and the group changed its name from MIX Acrobatics Theater to Formosa Circus Art, aiming to make contemporary connections to international practices in a contemporary context through exchange programs.

The group interacts with others through workshops on physical skills and creative thinking, with efforts also made to facilitate international networking. More time and work are needed in order to form a narrative composed of different technical circus acts, and FOCA has for now discovered the pattern of hosting two workshops first, before considering the potential for a co-production and making rehearsal arrangements. Those workshops hold a two-fold purpose. In addition to learning the skills and techniques from their overseas collaborators, those collaborators are also provided with opportunities to learn about the acts that FOCA members specialize in and their ways of expression. “We find international workshops quite beneficial, because we are able to personally come into contact with other creative talents and learn about their techniques,” says international affairs manager of FOCA, Yu Tai-Jung. Each international collaboration requires a least a year and a half or two years to execute, and the process is also highly volatile; for example, they had made plans to do a project in Cambodia, but it fell through because the local circus festival was cancelled. Therefore, a three-year grant is quite crucial for such an international exchange program. With this steady support, transitions are possible when a project takes an unexpected turn, and this was how the group’s “Circus Interdisciplinary Trilogy” came to be.

Interdisciplinary collaboration challenges how members of the group think about various logics of expression and presents opportunities for potential narratives to be formed, which can open up how circus art is considered. For example, I Have My Demons Have Me is a FOCA production in collaboration with British circus performance director, Timothy Lenkiewicz. It explored the topic of “fear”, which is rarely seen in circus performances. Departing from the performers’ personal experiences with fear, the performers also had to carry out vocal acts, an unfamiliar challenge for most circus performers. Through repeated and gradual trials and attempts, FOCA tried to discover various different possibilities for contemporary Taiwanese circus art and also to connect with their audience.

Timothy Lenkiewicz first learned about FOCA at the 2015 Edinburgh International Festival. FOCA was selected by Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture to participate in “Taiwan Season - Edinburgh Festival Fringe”, and Lenkiewicz saw FOCA’s performance there, which then led to their collaboration. Another one of their international collaborators was visual artist, Leeroy New, from the Philippines. They had met through the Taipei Performing Arts Center’s “Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance” (ADAM) in 2017, which shows how important international exchange platforms are for FOCA. Frequent visits to observe circus art festivals held in different places and to participate in performing art meetings allow for dialogues to be had on the international scene for circus art and to learn what the other creators are doing. For international networking, FOCA also contributes to the in-planning “Circus Asia Network” (CAN), as they exert effort to help the contemporary circus community in Asia to thrive, as well as to push for aesthetic experimentation and to expand the audience reach, seeking to find a balance between art and entertainment.

The international exchange practice of B.DANCE also departs from making in-depth observations of a particular setting; however, their case was prompted by a completely different opportunity. In 2014, the group’s artistic director, Tsai Po-Cheng, was awarded at the International Choreography Competition Hannover with the Gauthier Dance//Dance Company Theaterhaus Stuttgart Production Award for his work, Floating Flowers, and as the winner, he was given the opportunity to choregraph for Gauthier Dance, with the piece performed alongside the works of other prominent choreographers, including Hans van Manen and Alexander Ekman. He was able to immediately dive into doing creative work in Europe, and the European dance community also quickly learned about B.DANCE and their repertories. The group then received other performance invitations, and Tsai also received another production award. This led to a commissioned production from the Luzerner Theater, with the stage shared with Crystal Pite and Bryan Arias. Many found the experience quite incredible. “We were being watched closely by others,” says Tsai. Renowned dance magazine in Germany, Tanz, first observed them for three years before approaching Tsai for an interview. A lot of experiences were accrued before becoming an award winner; otherwise, it would be impossible to take on the production work when opportunities presented themselves.

Floating Flower by Tsai Po-Cheng in 2014 was a pure and pristine poetry with rich Asian imageries. Smooth, delicate and sensitive, it was full of unexpected delights and echoed the journey of life.

“They [the European audience] were quite curious about where we are from, our thoughts, and how do we see them,” explains Tsai. “Use your eyes to see what’s happening around the world and then make a response based on what you’ve learned.” This was his strategy for approaching the European dance community. For example, in Hugin/Munin, Tsai referenced a Norse mythology, but the style of expression was inspired by Japanese cinema, with attempts made to engage in a dialogue with the European audience. Reflecting on his practice in an international context, Tsai believes that “it’s not necessary to always try to find inspiration from deep within yourself. Your roots are what have nurtured you, and this is the kind of Taiwan where my generation has grown up in.” When working with international dance groups or choreographers, Tsai likes to observe them closely. “It’s not about seeing how they choregraph, but it’s about seeing everything that’s around them. What movies do they like; what are their favorite colors, and how do they think and communicate.” This kind of approach allows for a more comprehensive way to get to know the people and the art from that particular place. When participating in a competition, B.DANCE prefers to focus on interchanges and not on competition; fellow participants in the competitions later also became a part of B.DANCE’s network in Europe.

“We have to venture out to the world, and we also want to bring others in,” says B.DANCE manager, Hsu Tzu-Yin. Because of the support provided by the three-year project grant, the group was able to think about other possibilities besides touring, where they can make deeper connections and also strengthen the way they train. With the support from NCAF, the group proposed a three-year co-production project, with guest choreographers invited to work with Tsai and B.DANCE dancers, with programs created respectively and presented on the same night. The project also became more in-depth as the years went by. In the first year, a guest choreographer from Luxembourg was invited, and in the following year, in addition to choreography-oriented collaboration, four Taiwanese dancers worked with three Spanish dancers and co-created the program, MILLENNIALS. At the same time, emphasis was also placed on experiences of other ways of living, with a month-long residency arranged in Spain, where rehearsals and performances were held. The exchanges in Europe made the dance group realized that they hope to provide their dancers with reasonable pay, so they could focus and deal with their work under better circumstances. The interchange also provided a diversity that was missing from the dancers’ former training.

Redefining Artistic Practice in the Face of Shared Challenges

The international exchange project carried out in recent years by HORSE also aims for long-term, two-way development, and furthermore, with effort also made to redefine “exchange” and how artistic work is realized. The group’s artistic director, Chen Wu-Kang, and internationally renowned Thai dancer, Pichet Klunchun, met in 2016 at a forum organized by the Ministry of Culture, and they were able to embark on a preliminary collaboration through the support made possible by “The Emerald Initiative” (Guidelines and Procedures for Grants for Cultural Exchanges and Collaborative Projects with Personnel from Southeast Asia). According to Chen, Pichet Klunchun frequently receives similar international invitations, and the reason that they were able to go from an initial exchange to working together on the production, Behalf, which further led Rama’s House, a three-year project supported by NCAF, besides the help from the Ministry of Culture and dramaturg Tang Fu-Kue that connected the two sides, it was also because they have elected to work under a model that seeks to dive deep into everyday life and culture. This approach allowed Pichet Klunchun to realize that this project differed from other production-oriented collaborations, and the process allowed for “things to continue to emerge”, which prompted Pichet Klunchun to willingly invest more time in this project.

For Rama’s House, the two creators visited prominent traditional dance masters in Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Indonesia, where the legend of Ramayana is quite popular throughout these four countries. They learned from those masters on dance and also learned about the context and the history of their respective local traditional dance heritage. After conducting field surveys and research for two years, the interviews and archives gathered from their dance journey were exhibited, which concluded with the four masters invited to perform in a forum-like setting, breaking the conventional expectation of stage performances.

Similar to how readymade was confronted in contemporary art, the two also opted with a different path to consider corporeality and dance. Besides rehearsing, what else can be pursued after through creative work? Throughout the collaborative process for Behalf, the two spent time together; they would do warm-ups, study, and discuss, and they also lived together, where they learned about Taiwan and Thailand. Incredibly, the basic structure of the dance repertoire was completed on the second day after they had settled in Thailand. “If it wasn’t due to the energy that we were receiving from around us, I doubt that we would’ve been able to work on it so rapidly,” explains Chen. “The interchanges we had is the work itself; it pays to spend all those time together.” He further explains that this concerns the entire team, as well. Having international collaborators on board like the dramaturg and the lighting desinger during the co-production process of Behalf made Chen realized that the team can also be a part of the creative process. They are not just there to support the concept of the artist, and he was able to gain such insight through thisinternational exchange opportunity.

No longer bound by the need to justify one’s work by endless rehearsals, Chen and Pichet Klunchun focused on the traditional forms of dance in those four Southeast Asian countries they had visited and the complex relations and interactions between history and religion. They contemplated on the issues of origin, and while examining traditions, they analyzed and speculated on how today’s body traditions came to be. For example, how Ramayana is interpreted in traditional dance embodies interconnected factors of religion, politics, nature, the heritage of performing art and ways of living. Therefore, in order to examine the contemporary body, these contextual factors needed to be studied.

The interactions between the two collaborators broadened the horizons of their art practice. According to Chen, because of the various international exchange experiences, he was able to take on a broader definition for what constitutes as a dance group. We Island Dance Festival that HORSE co-organized with OISTAT (International Organisation of Scenographers, Theatre Architects and Technicians) or the series, Primal Chaos – Dance × Sound Improvisation, which they collaborated with improvisational musicians, were endeavors that differentiated from the group’s previous oeuvre. “After completing an outreach organized by the Asian Cultural Council, I saw that our rehearsal space was vacant, and I thought something should take place there, which led to the planning of Primal Chaos…We are just trying to make the best of what we have.” Ther exchange experience has allowed HORSE to gain new awareness and engage in new explorations inartistic processes, as well as in organizational operation.

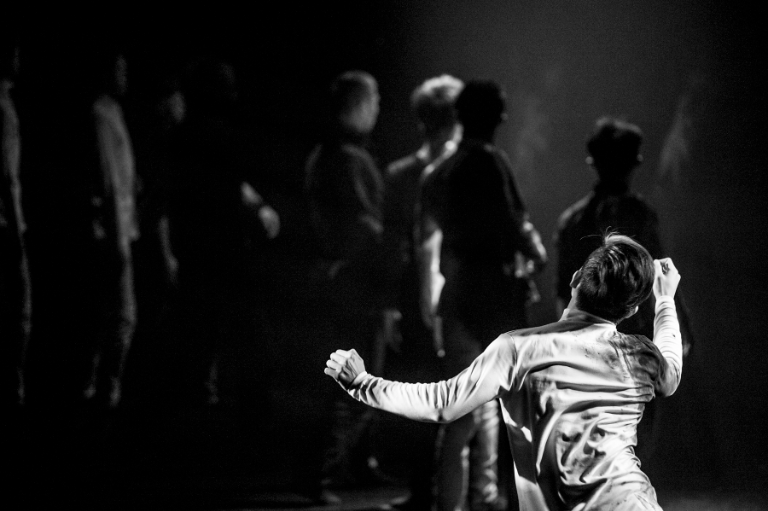

The Primal Chaos – Dance × Sound Improvisation series in 2016 was unbounded and full of life. The heterogenous practices of the participating arts opened up new dynamics between sound and dance.

The exchange projects carried out by the aforementioned groups all pointed towards multifaceted interactions and explorations beyond just performing on stage. Such development are connected to changes in subsidies structures and in the understanding of art in recent years. On the other hand, international exchanges beyond stage presentations have been happening for decades without being sufficiently discussed and documented. Body Phase Studio, which was founded in the 1990s, is one of the groups that has been organizing this kind of exchange for years. “The influx of international exchange and showcase platforms (such as big market meetings and the countless festivals out there) exposedthe insufficiencies and the lacking of perspectives of some practices,” says Yao Lee-Chun, who has been in charge of the Body Phase Studio and the Guling Street Avant-garde Theatre since 2008.

Looking back at its collaboration mechanisms applied in the past decade, self-produced programs in the Guling Street Avant-garde Theatre usually involve cross-cultural exchanges, thanks to Body Phase Studio’s pursuit of artistic inspirations and its engagement in the explorations of art forms. However, when only general grants and limited funding are available, Body Phase Studio tends to focus on projects that can allow individual artists to freely exert their potential while engaging them in every aspect of the production process. “This approach can lead to more continuity, compared to the concept-oriented curatorial approach which demands the artists to fill in its design,” says Yao.

For example, the project, “Theatrical Reader”, was originally initiated because they realized that such event could reach a different audience through the participating artists’ personal network, including art students that usually don’t attend art events held in the south part of the city. After the first two smaller-scale iterations of the event, “from the point of view of listening, we realized that anything could be read out loud.” For example, one of the ensuing iterations choseconnections to “tradition” as theme, and it led to the prototype of The Sewing of Time by Cheng Yin-Chen of Approaching Theatre. The work was later invited to perform at a festival in Macau, followed by further experimentation conducted at the Songyan Creative Hub and a performance given at the Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama (TPAM). The 6th iteration of “Theatrical Reader” featured the theme of “Body – Space – Asian Texts”, and Tseng Jui-Yuan was invited to host a workshop on “motif writing” and “labanotation”, with reading done through movements of dance. In the same year, two Japanese chorographers were invited to read through body movements, acquainting both the theater makers and the audience with alternative paths of expression.

The 6th “Theatrical Reader” held in 2017 continued to promote emerging local talents of theater, and while expanding to connect with Asian texts, it also placed focus on the body’s declarative expressiveness. Through body-text writing and cross-referencing, possibilities to clearly read aloud complex lexicons were discovered. (Stage still of No One Talks Anymore at the 6th “Theatrical Reader”)

Yao mentions that a certain level of team building is needed in Taiwan in order for in-depth international exchange to take place. “Many opportunities in the past could not be sustained because of lack of a team or the idea of establishing a platform, without which international exchanges could hardly happen.” The composition of the group is also quite crucial, which is why Body Phase Studio has always emphasized training and fostering team members. People may not stay in the group all the time. Even so, “the talents we fostered can be future collaborators in other ways, so it wouldn’t all fall apart after one particular project. ” More importantly, such alliance in a broader field is necessary for responding to waves of thoughts internationally. In the Sixth Sense in Performance Arts Festival, physically impaired international artists were invited to perform; and for EX!T - Experimental Media Art Festival in Taiwan, expanded cinema was introduced which inspired other sound art performances . After Body Phase Studio became a resident group at the Guling Street Avant-garde Theatre, the people involved have been able to stay on top of the constantly evolving concepts and able to form an international exchange base, despite having very limited funding. “Many of the young people in Taiwan need experiences like these; beyond just visiting a place, they need to tangibly take part in the technical aspects which made the performance possible.”

“The operations of artist villages (another key aspect of the development of international exchange in Taiwan) have opened up different perspectives for people,” says Yao. The artist village model allows people to further see that to operate a space like this involves “more than just productions, and it certainly involves more than just making one’s own productions.” What it embodies is a sense of publicness, with external and internal ties formed at the same time. Yao further explains, “Such awareness is prerequisite for international exchanges…It may take a long time before a collaboration with artists we come into contact with in artist villages or through various residency programs to materialize; yet the process itself is already quite different from simply buying a program.”

Based on the international experiences of the aforementioned seven groups, we can see that increasingly more groups are now aware of the importance of operating their own space or team building; they are no longer just looking at the productions they create. With the project grants from NCAF , more groups are able to devote themselves in such multi-layered pursuit, allowing a different understanding of international exchange beyond that of touring to take shape. The Century Contemporary Dance Company and Body Phase Studio, two groups that have started international exchange earlier than others, have focused on fostering individual members as a path to break through the funding challenges and deepen the exchange. From these examples, it is also observed that the set up of the exchange program, as well as the reward from it are perpetually interconnected with the group’s artistic and operational objectives.

The various practice carried out by each group allows us a diverse view of what performing arts encompass. It concretizes the “context”—and makes this rather abstract term specific. International exchange most likely involves more than just two countries. The interchange often involves negotiations between traditions, cultures, disciplines, as well as communications between organizations, markets or even between discursive systems. When an art grant institution advocates for long-term and in-depth international exchange, the space is opened up for performing arts groups to make different proposals which not only will develop their potentials, but eventually will explore and redefine the performing arts, as well. Beyond what’s presented on stage and more than just venturing out, these practices of international exchange also shape the development of contemporary performing arts.

*Translator: Hui-Fen Anna Liao

More OUTLOOK