The National Culture and Arts Foundation (NCAF) supports music composition by Taiwanese composers, and has accumulated many works through its regular grants for "Original" and "Commissioned Compositions" over the years. In addition, under the Music categories of "Performance", "Curatorial", "International Cultural Exchange", and even the newly-established "Art Advances", there are many grant recipients that focus on the creation of distinctly-Taiwanese works. Although the overall arts and cultural environment remains challenging, it is gratifying to see that, thanks to the hard work of many parties, local creativity and performances continue to blossom.

In the past, except for instrumentation, length, and deadlines, commissioning institutions seldom made any demands on the composers when it came to subject-matters. However, the author observes that in recent years, greater importance is attached to planning concepts in the preparation stage of concerts to drive ticket sales, while program selection is also aimed at fitting specific themes. Therefore, when inquiring about composers' willingness to collaborate for certain productions, commissioning institutions will discuss the theme of the commissioned work with composers beforehand in the hope that the music can match the theme of the concert. The commissioned work will then be included as a centerpiece in the concert's publicity.

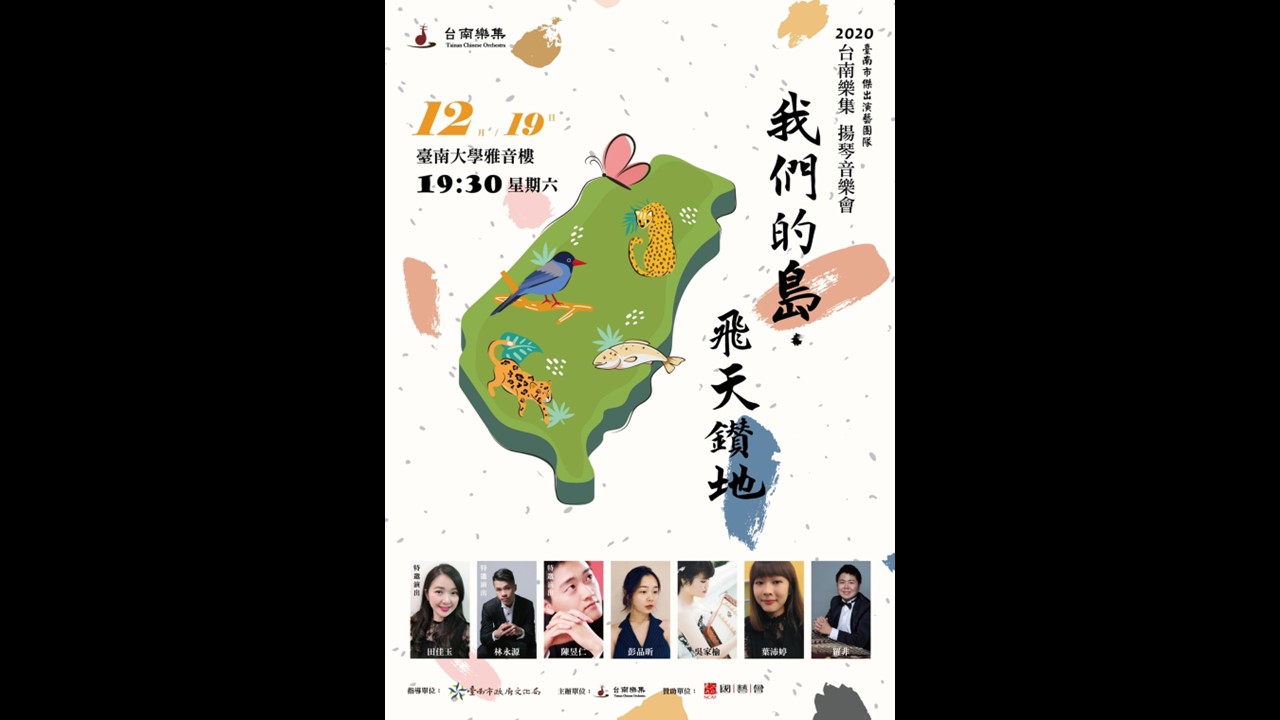

To attract local audiences, among the various innovative and diversified concert themes, the number of applications under the Music category with concepts derived from Taiwan's local customs, culture, history, and landscapes is gradually increasing. It can also be seen that the composers applying for Commissioned Composition grants are also given the task of responding to the concepts of the program and composing music under the framework of the concert theme. For example, for Tainan Chinese Orchestra's 2020 "Our Island, From Sky to Earth" "Yangqin Concert", composers were commissioned to create works inspired by Taiwan's endemic animal species. It included the composition of Wan-Yu Chang, inspired by the Formosan clouded leopard: Clouded Leopard's Thoughts; and the work by Chung Jen composed for the butterflies and moths of Taiwan: Teasing fire In 2021, the theme of Müller Chamber Choir's concert was "Our Land, Our Songs", premiering the composition of Chen-Hui Jen, inspired by the sceneries of the subtropical island of Taiwan: Voices from the Twilight Islands. In Taipei Percussion's 2022 concert "City lights Taipei", they played Ya-Wen Lien's work Rhapsody - Taipei, a piece portraying the agitated uneasiness of Taipei City during the pandemic. In Formusica's concert series titled "Piano Music from FORMUSICA", the theme of 2022 was "The Sound of Taiwan", which was presented alongside projected illustrations. The concert included a work by Chin-Yow Lin, in turn inspired by Yaw-Chien Fang's Taiwanese Hokkien poem The Golden Zengwen River, the unaccompanied violin piece Memories of My Beautiful Hometown - The Golden Zengwen River.

Tainan Chinese Orchestra's "Our Island, From Sky to Earth Yangqin Concert" program cover

Of course, in addition to commission requirements, composers will also spontaneously choose creative materials that are related to local culture or traditions. Some of the applications that have received grants under the Original Composition category in recent years include: Hsien-Sheng Lien, inspired by traditional worship rituals, created Nankunshen, a piece for triple-woodwind symphony orchestra to depict the carnival-like atmosphere of the Wangye Ceremony held at the Nankunshen Temple in Tainan during the fourth lunar month. In Nanguan music, the gongche notation only shows the main or "skeletal" melody—the unique heterophonic feature of filling in the melodic space and rhythm during performances inspired Yu-Hsin Chang to compose Amaryllidaceae for six female voices, violin, viola, cello, and piano. Fang-Wei Luo, inspired by the poem Listening to Winter in A Spring Night by Taiwanese poet Li Chen, incorporated the concept of "Song without Words" and created Songs of Desolation for classical guitar, reciters, and interactive electronic music. Shiuan Chang's family ran a martial arts school, and his childhood memories of watching his grandfather practicing the moves were combined with Laozi's Tao Te Ching, which expresses the idea of "lingering as if having a solid existence, allowing for inexhaustible use". This became the source of inspiration for his percussion solo work GU SHEN.

As can be seen from the above examples for "Original" and "Commissioned Compositions" related to Taiwan, the pieces are inspired by a wide range of subjects, from traditional ceremonies and theater, to nature and the environment, literary works, family memories, and even contemporary urban landscapes. The instrumentations included solo instruments, ensembles, chamber works with voice, percussions, choir, and symphony orchestra, as well as Chinese and Western instruments and electronic music. The composers belong to different generations, and there are also composers who have been living abroad for a long time.

In response to the recent increase in the number of applications for creative grants based on the concepts of traditional music or local cultural and historical heritage, this study utilizes the Taiwan Composers Database in the NCAF Online Grant Portfolio Archive to compile a list of composers who have received project grants in recent years for Original or Commissioned Compositions with themes related to traditional culture, as well as Taiwan's local customs and traditions. To understand the philosophies of composers of different generations, seven composers were interviewed: Chiu-Yu Chou, Shih-Hui Chen, Heng Chen, Yun Lu, Ching-Yu Hsiau, Shan-Hua Chien, and Tsung-Jen Hsieh. The ages of the interviewees spanned a wide range, with the most senior being Shan-Hua Chien, who was born in the 1950s, and the youngest being Heng Chen, who was born in the 1990s. All seven composers have studied abroad, with five of them returning to Taiwan after their studies, while Shih-Hui Chen and Heng Chen settled down in the United States and France, respectively. Through this interview, we examine the influence of these composers' upbringing and life experiences on their creative endeavors. We also focus on the projects supported by the NCAF grants, inviting the composers to share their perspectives and specific details of their creative process.

Each composer has their own unique listening experience due to the differences in family education, generational background, or school environment. What non-Western musical influences left a deep impression on you when you were growing up?

The family of Shih-Hui Chen's grandmother ran a hotel in Badu, Keelung. As a child, she watched the noontime Taiwanese opera and Taiwanese hand puppetry shows on TV almost every day. Her father, who loved Peking opera, would often take her to the National Army Hero House and the National Kuo Kuang Academy of Arts (now the National Taiwan College of Performing Arts) in Muzha to watch performances. Although she couldn't fully appreciate the artistry at the time, it left an indelible mark on her memories. When she was studying at the National Taiwan College of Arts (now the National Taiwan University of Arts), even though Chen was a student in the Western Music program, the room where she practiced was next door to practice rooms belonging to the Chinese Music program, and she often heard the students majoring in pipa (Chinese lute) practicing the ancient pipa piece Ambush from All Sides repeatedly. By chance, when she heard the pipa virtuoso Man Wu play the same piece at a concert in the U.S. many years later, it unexpectedly evoked a sense of homesickness in her. In 1999, she wrote her first solo work for a traditional instrument—the pipa composition Fu I.

Shan-Hua Chien responded that when he was studying at the National Taiwan Normal University in the 1970s, as music education was still completely Western-centric and there were almost no classes on traditional music, there was only one course on non-Western music, "Introduction to Chinese Music". Despite this, he decided to go teach in Orchid Island after graduation. At that time, Orchid Island's traditional culture had not yet been influenced by the outside world and still retained its original pristine form. When he first heard the traditional music of the Tao people, it made a great impact on him, as if he had discovered a world of music that was completely different from what he had learned in the past, and he was deeply attracted to it. So he used his spare time to visit the various indigenous communities on Orchid Island to collect material. This experience had a great influence on his future creative career. He then went to the U.S. for further studies, and after returning to Taiwan, he continued to visit the indigenous peoples around Taiwan to conduct relevant fieldwork in order to preserve and document their music to this day. He also actively participates in activities of the Asian Composers League, which further broadens his horizons. The league takes turns to organize annual conferences in each member country, and in addition to concerts and seminars, the host country also introduces its unique music traditions through special demonstrations and lectures.

Currently residing in France, Heng Chen’s parents are avid lovers of traditional arts and culture. From a young age, he regularly attended Peking opera and Kun opera performances, which enriched his cultural and aural experience. When he was a student at the Affiliated Senior High School of National Taiwan Normal University, he took on erhu (Chinese two-stringed fiddle) as an elective. This also helped him to appreciate the unique charm of traditional musical instruments that differed from that of Western instruments.

Chiu-Yu Chou was deeply impressed by the music program curriculum of her school, the Kaohsiung Municipal Hsin Hsing High School. At the time, the head of the music program, Ms. Chin-Ai Hung, once designed a homework assignment that required her students to listen to a recording of a Kun opera performance, transcribe it, and mimic the singing voice during the exam. Ms. Hung also recommended traditional opera performances to her students and encouraged them to appreciate the music. Although Chou only had a superficial exposure to this genre, it broadened her musical horizons, and when she entered the Taipei National University of the Arts, she actively tried to learn more about traditional music. In her second year of high school, she participated in a composition camp organized by the Provincial Symphony Orchestra (now the National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra), which made her consider incorporating traditional elements into her music compositions.

Growing up in Taichung, Ching-Yu Hsiau believes that the cultural environment of her hometown has had a natural influence on her music, but it’s hard to put into words. She mentioned that after studying in France, she realized that the spatial design of her compositions was influenced by her mother tongue, and gradually began to emphasize rhythm and breathing in her music. At that time, she was taught by the Japanese composer Yoshihisa Taira. Influenced by her teacher, Hsiau began to explore musical meanings with an Asian mindset, focusing on the delicate mixing of timbre and paying close attention to the overall sense of flow in her works. In addition, the experience of taking erhu as an elective in Taiwan was the starting point for her increasing intimacy with traditional music. When she was in her second year at National Taiwan Normal University, Professor Tsang-Houei Hsu, the instructor of "Introduction to Traditional Music" at the time, set the guqin (Chinese zither) composition Youlan (or Solitary Orchid) as a piece for her final exam analysis. The inward-looking and exquisite inflections of this classic piece were unforgettable to Hsiau. Many years later, when she composed her solo piano work Le Phénomène de la ligne V, she incorporated the melody of Youlan and used it as the core of the pitch structure.

Tsung-Jen Hsieh recalls that when he was studying at the National Academy of Fine Arts (now the Taipei National University of the Arts), in the "Harmonics" class for composition students, Professor Nan-Chang Chien used to ask students to think about whether or not their compositions should incorporate local elements. This question planted a seed in his mind and he continued to search for his own answers while studying in Germany. In addition, he still maintains the habit of playing the guqin because studying the guqin in university was a very special experience for him. He recalls that when he first came into contact with the guqin, he was just casually plucking the strings, but the vibrations from his fingertips felt like they were flowing down his bloodstream and going straight to his heart, something that he had never experienced before when playing any other Western musical instruments.

Among the people interviewed by the author, Yun Lu has quite a unique background. She started playing erhu from a young age, and since she was eight years old, she would go to China with her parents to receive training in traditional music during summer vacations. However, when she was studying in Taiwan, the music education was more westernized, so it seemed to Lu that Asian traditional music and Western classical music were two parallel lines. It wasn't until she went to university and studied composition with Professor Chung-Kun Hung that she began to apply composition techniques of Western academic music to traditional instrumental music, and felt that the two worlds had finally intersected. Traditional music has a deep cultural heritage that fascinates Lu, but although she appreciates the soundscape works that utilize a lot of extended techniques and defamiliarized timbres, she doesn't follow this route in her own compositions. She prefers to preserve the idiomatic practice of traditional instruments and to explore their unique textures, expressiveness, and emotionality.

Tell us about your past compositions related to traditional music or elements of Taiwanese culture, and whether you have encountered any special requests from a commissioning institution in terms of the theme?

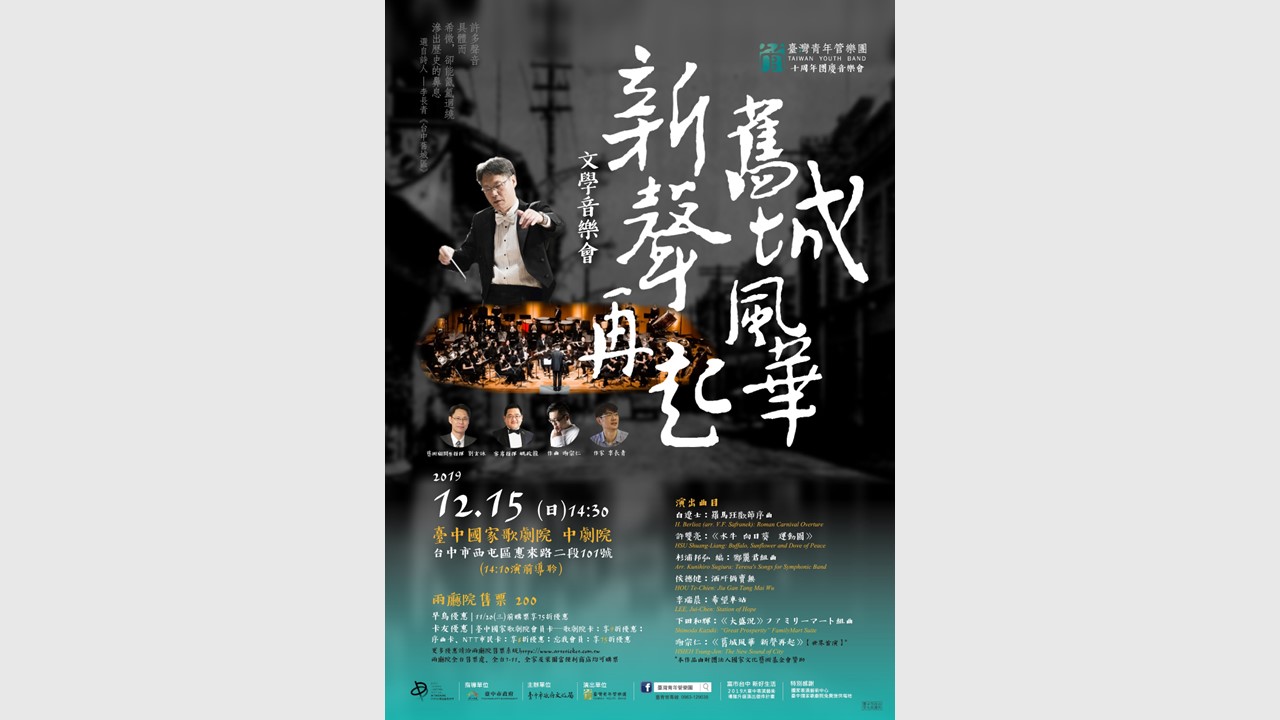

The Taiwan Youth Band, based in Taichung commissioned composer Tsung-Jen Hsieh to create music with Taichung City as the theme for two consecutive years. The first time, he used Taichung's literary scholars and works as his source material, choosing Kui Yang, a writer who lived in Taichung for half a century, and his work The Uncrushable Rose. Through the music, Hsieh conveyed the unique sense of time that he experienced while reading Yang's writings, and composed an orchestral piece that does not follow the traditional strategy of a linear progression. The second time was in 2019, when the Taiwan Youth Band moved the administration office to a new location near the intersection of Ziyou Road and Zhongshan Road. It happened that Hsieh had also moved somewhere in the vicinity of the Taichung Second Market, not too far away from the office. The Central District of Taichung City used to be the heart of the city's thriving business center during the Japanese colonial era because of its location as a transportation hub. However, with the decline of the business district and the population, a large number of the buildings in the area have been left empty. Hsieh mentioned that after he moved to Central District, he often observed the old houses brimming with stories during his walks. The lack of maintenance has made the building facades dull and faded, leaving behind traces carved by the passage of time. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Taiwan Youth Band in 2019, the orchestra filmed the old city district and interviewed several shopkeepers in the neighborhood. The footage was edited into a short film and screened before the premiere of the composition to further heighten people's experience of the work. According to the theme of the concert, Hsieh composed The New Sound of City, weaving historical melodies into a new soundscape to evoke the old city's unique, leisurely atmosphere and collective memories. It was very well-received by the audience.

Performance poster of the Old City Splendors, New Voice Rises Literary Concert by Taiwan Youth Band

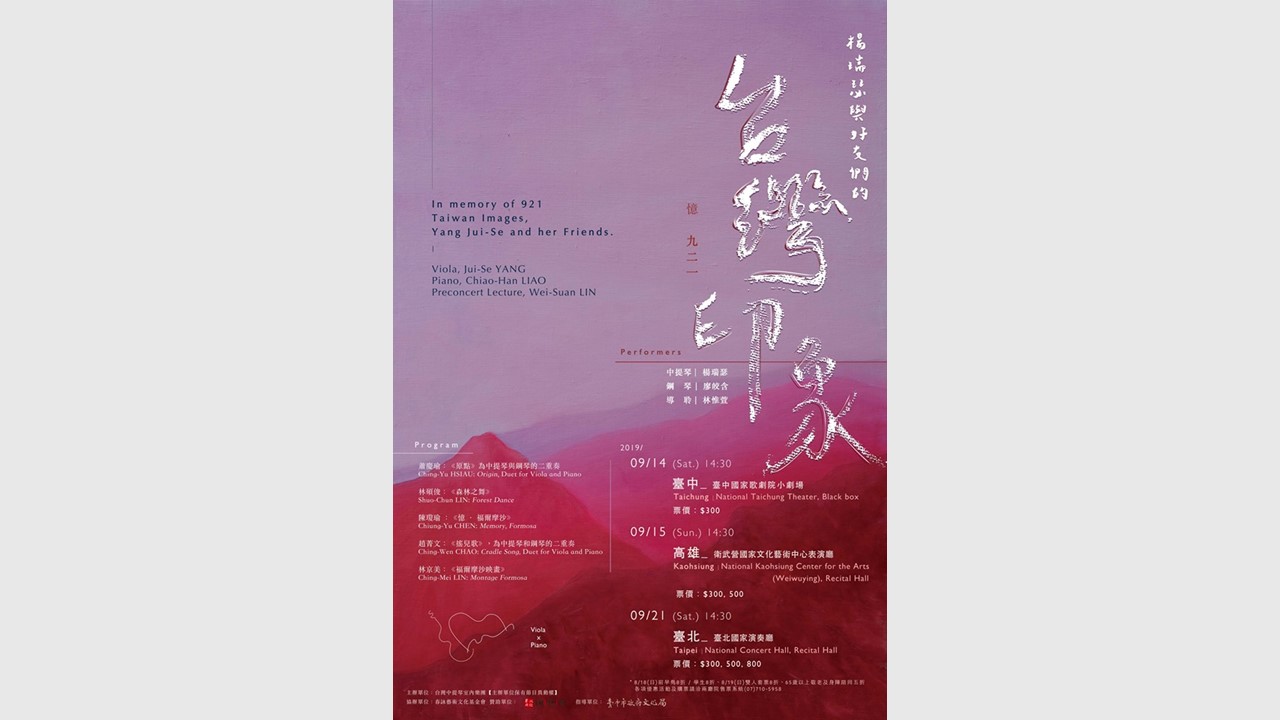

In 2019, Ching-Yu Hsiau was commissioned by viola maestro Jui-Se Yang to compose music based on a new arrangement of Taiwanese folk songs. The concert Taiwan Images, Yang Jui-Se and her Friends was to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the 1999 Jiji Earthquake. As Hsiau hoped to provide comfort to the people through her work, Origin, she chose to base her composition on a more tonal vocabulary, as well as used the contours of the 1970s Taiwanese pop hit Love Trip and the Bunun hymn Kipahpah Ima. She hoped to create a piece that would fulfill the artistry threshold of contemporary music, yet didn't stray far from the easy accessibility of pop music, so that it could resonate with a wider audience. The soprano solo Three Poems by Lin Cheng-Mou, completed in 2014, is a very special work. Ching-Yu Hsiau chose three poems in Taiwanese Hokkien with bird themes from the works of poet Cheng-Mou Lin. These are Ba-Hioh (Eagle), Night Heron, and Sparrows from the Mountaintop, as well as excerpts of works by the French composer Olivier Messiaen. Messiaen was a bird enthusiast. He roamed the fields and forests for many years and recorded a large number of bird songs, composing many works with bird songs as core elements. "Ba-Hio̍h" means "eagle" in Taiwanese Hokkien. Hsiau extracted a fragment of "Milan noir" (the French word for "eagle") from Messiaen's La Fauvette des jardins, and transformed it for use in the piano part of "Ba-Hioh". The soprano's voice imitates traditional Taiwanese opera tonal elements, with a slight pentatonic coloration in its pitch structure. Ching-Yu Hsiau's ingenious design allows for the interweaving of the two very different pitch elements, resulting in a work of great dramatic expressiveness.

Poster for the "Taiwan Images, Yang Jui-Se and her Friends" concert by the Taiwan Viola Chamber Orchestra

In 2022, when the Yung Yue Chi music ensemble commissioned Shan-Hua Chien to compose a vocal piece, they requested that the poetry of Taiwanese poet Han-Shiou Lu be used as the source material. Chien read Lu's collections of poems over and over again, and after much deliberation, he decided to use two Taiwanese Hokkien poems, Budai Xi Suite and Taiwan to compose the music. One of the reasons he chose the Budai Xi Suite was because the Affiliated Elementary School of the Hsinchu College of Education was quite a distance away from Chien's childhood home, and he had to take the bus to school every day. There happened to be a temple right by the school, where Taiwanese opera troupes and traditional hand puppetry troupes used to stage performances for temple celebrations. Although he could only watch fragments of the shows while waiting for the bus, he always gave his utmost attention during that quarter-of-an-hour waiting time. Over the years he learned the performances by heart, and they have become precious memories of his childhood. Therefore, in the Budai Xi Suite, he used the elements of the Luogu percussion ensemble to emphasize and echo the tradition of Taoist music in traditional musical theater. In addition, Chien has devoted himself to the study of indigenous music since his youth, with a particular focus on Austronesian music. He has visited many indigenous communities over the years. As soon as he read the lines of the poem Taiwan, many creative ideas immediately sprang to mind. Instead of literal quotations, he used some musical concepts from the Austronesian peoples, such as cyclic repetition and layering, to transform the imagery of the poem through music.

Chiu-Yu Chou wrote Wild Graffiti during her first year of PhD studies in Manchester, England. As a major city in the development of the modern industrial revolution, Manchester is home to a variety of contrasting architectural styles, including Victorian-era buildings with refined and elegant facades, post-modernist skyscrapers soaring into the clouds, and historical red-brick textile factories, all intertwined with colorful graffiti seemingly painted at random in the streets, but which convey subcultural connotations. Chou uses the title "Wild Graffiti" as a metaphor for the cultural shock she experienced as an outsider during her stay in the UK. It was only after four years in the UK that she finally integrated into local life. However, when she returned to Taiwan in 2013, she realized that she had to adjust her frame of mind to Taiwan's mindset and culture. In 2020, when Chou received a commission from the Taiwan Music Institute for a project titled "Taiwan Music Image", she recalled this shift in his perspective and composed Wild Graffiti III. This is a mixed Chinese and Western composition for dizi (transverse bamboo flute)/xiao (vertical bamboo flute), erhu, pipa, guzheng (Chinese plucked zither), and cello, depicting the reverse culture shock that she underwent when she returned to Taiwan after her graduation. Each section of the piece has a different texture, reflecting evolving mindsets. Beginning with the sea voyage, the outline of the island of Taiwan gradually emerges from the clouds and mist. Then, Chou uses the heterophony technique of Beiguan music, depicting the sounds of temple celebrations that can be faintly heard from the shore as we approach land. She borrows the concept of the Bunun eight-part chorus as we move towards the verdantly-forested inland, symbolizing the continuous unfurling of the mountainous terrain. This is akin to the long history of Taiwan, which contains the wisdom of the ancestors and the diversity of cultures.

What are the concepts and experiences of composing for traditional instruments or ensembles including both Chinese and Western instruments?

Traditional music and Western classical music have different development paths and distinct cultural connotations. In the first half of the 20th century, Western art music was characterized by many innovations in terms of compositional structure, expansion of musical concepts, and pitch and rhythmic design. Composers also attempted to explore new sonorities through the use of extended techniques and special instrumentation, which became even more prevalent after the end of World War II. In contrast, Asian traditional music has had a late start in this area. However, after studying in Europe and the United States, Taiwanese composers such as Tsang-Houei Hsu, Shui-Long Ma, Hwang-Long Pan, and Deh-Ho Lai began to integrate Eastern and Western musical elements and philosophical thinking into their traditional instrumental works, and also started to write for ensembles mixing Chinese and Western instruments. Hwang-Long Pan's East and West series is a representative work, and Shui-Long Ma's Pipa and String Quartet set a model for the future "Spring Autumn Music" concert series.

Traditional and Western musical instruments carry their own profound cultural heritage, with different idiomatic practices, timbral characteristics, and temperaments, as well as different logics and aesthetic connotations in the development of the classical repertoire. Therefore, when composing for traditional instruments, composers have to have different considerations than when using Western instruments. When creating mixed compositions of Chinese and Western instruments, bridging the gap between Chinese and Western instruments in the work, or the opposite, highlighting the heterogeneity of each instrument are issues that need to be considered. No matter what strategy the composer chooses, they will face the peculiar challenges when using both Chinese and Western instruments.

The theme of guzheng player Jing-Mu Kuo's concert in 2020 was "Not Equal to". He commissioned Chiu-Yu Chou to compose a duet for guzheng and cello, The Emergence of Adhyāśaya. Inspired by the phenomenon of emergence in biological systems, Chou combines the experience of meditation with the exploration of the diverse possibilities of musical element development. She attempts to start from tiny, fragmentary musical motifs that interact with each other over time to reveal a new appearance, a phenomenon that echoes the theme of the concert, "Not Equal to". In this piece, the guzheng uses an alternative tuning, while Chou uses the placement of foreign objects to expand the range of timbral expression. However, due to her fondness of the tonal qualities of traditional guzheng music, she mostly retains familiar guzheng techniques except for some passages in which she draws metal cups or a violin bow against the strings of the guzheng to produce sound. Not too many extended techniques are applied to the cello except for the concluding section. Through the dialog between guzheng and cello, Chiu-Yu Chou’s delicate mixing of acoustic layers leverages juxtaposition and contrast to demonstrate the uniqueness of each instrument.

Heng Chen's works are subtle and brimming with vitality. When discussing the idea of composing pieces combining Chinese and Western music. He believes that it is not necessary to pursue uniform compatibility, but rather to objectively use Western and traditional instruments as a medium of expression in line with the context of the piece. Different compositional strategies can be flexibly applied for individual passages. For example, in some passages, Western instruments mimic the unique vocabulary of traditional instruments, even disguising their original characteristics to certain extent. In certain passages, traditional instruments adopt the performance techniques of Western instruments, breaking free from established concepts to reveal new yet unfamiliar timbres. In other passages, one can try to blur the line between Western and Eastern instruments and use syntax as a bridge to explore the possibilities of intertwined timbres and to showcase homogeneity and heterogeneity between the two instruments.

Although Yun Lu grew up in the highly-urbanized Taipei City, the percussion and wind ensembles that parade through the alleys and streets during temple festivals left a vivid impression on her, and have provided her with many inspirations for her future musical creations. As a student, she majored in erhu, which has led her to becoming fascinated by traditional opera, and she has used elements of Beiguan music in her compositions on many occasions. This practice reveals her areas of interest and her close connection to traditional culture. At first, Lu did not study Beiguan music systematically, but simply wanted another method to introduce her music to the audience. Therefore, she borrowed a few lines of Beiguan tunes as motifs for the suona concerto Lang Sai (Dancing Lions). However, during the composition of Lang Sai, she began to understand the distinctive charm of Beiguan, which inspired her to properly study the features and functionality of the various qupai (fixed melodies), exploring how to use different combinations to apply to her own creations. In her 2015 Golden Melody Awards-winning piece for Chinese orchestra, The Folk Parade, with tradition as the foundation, she not only utilized the unique syntax of Beiguan music, but also borrowed large portions of the Beiguan qupai repertoire. The following year, when the Golden Melody Awards commissioned Lu to compose The Calling for the award ceremony, she took the challenge of presenting it in the form of musical theatre, echoing the dramatic elements embedded in the piece and strengthening the layers of musical expression to reveal a more intense, more powerful display. Lu's aforementioned suona concerto, Lang Sai, has not only been highly acclaimed by the Taiwanese Guoyue (modernized form of traditional Chinese music) sphere, but has also been performed many times by orchestras abroad, such as in Singapore, China, and Hong Kong. In Lang Sai, there is a passage that portrays the unique custom of setting off beehive firecrackers in Yanshui, Tainan, during the Lunar New Year's Eve every year. Lu said that when performing in Taiwan, Taiwan's Chinese orchestras have always been able to convey a stunning scene of the beehive firecrackers going off, allowing the audience to experience the frenzied excitement of the night sky lit up by the flames of thousands of fireworks whilst in the concert hall. Intriguingly, when Lu shared her experience of listening to Lang Sai performed by overseas orchestras, these orchestras seemed to have difficulty in mimicking the excitement of the beehive firecrackers being set off and lacked that "Taiwan flavor" that so exhilarated the local audience.

After penning several compositions with traditional instruments in the United States, Shih-Hui Chen wanted to find a more authentic Taiwanese sound. In 2010, with the support of the Fulbright Program, she came to Taiwan for research, spending nearly two years learning from masters at Nanguan centers. The first work she practiced was A Plea to Lady Chang'e, a three-minute piece that took her three months of continuous study before she was able to sing and play it herself. The experience of learning Nanguan songs had a great influence on her subsequent compositions. Although she had already been using traditional elements in her works, in retrospect, she believes that researching audio data or music scores at that time was still a rather indirect way to achieve her composition goals and it was still within the framework of Western training. However, after learning to play Nanguan music, Chen was finally able to internalize the traditional elements, and realized that the method of notation that she was accustomed to before was no longer sufficient for her to express the meaning she wanted to convey. Thus, in 2013, she adapted a more free and flexible notation method when she wrote A Plea to Lady Chang'e for String Quartet and Nanguan Pipa. It was nearly a decade ago that Chen returned to Taiwan to study Nanguan, and at present, she has changed her mindset once again. She is of the opinion that instead of denying her long-term training in Western music and pursuing "pure" Taiwanese music, she should now incorporate diversified elements into her works and break through the monocultural framework. Her aim is to deliver the message that "Taiwan is a part of the world" through her music. Her current work, Kimchi, Pickle and Wine, is an attempt to interpret the commonalities of global cultures through music, inspired by the fermentation process that is part of the everyday diets of ordinary people across various regions.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of grant applications for compositions based on traditional music or local cultural and historical elements. What are your thoughts on this phenomenon?

Most of the interviewed composers are optimistic about this phenomenon because they believe that music can reflect musicians' interest in traditional culture and Taiwan's contemporary society. However, some composers are concerned that if NCAF puts too much resources on this type of applications, it may lead to a situation where cultural policies would start to affect the development of the arts.

Shan-Hua Chien believes that for composers living in Taiwan, finding inspiration and materials from everyday experience comes quite naturally. He cites his own work as an example. When he was commissioned by ISCM-Taiwan to compose the cello piece Retrospect for Cello Solo in 2021, he used the school anthem of the Affiliated Elementary School of the Hsinchu College of Education (now the Affiliated Experimental Elementary School of National Tsing Hua University), which he attended as a child, as pitch materials. But he didn't regard it as a Taiwanese or traditional element, but simply utilize the musical materials he came across while growing up in his works.

Tsung-Jen Hsieh believes that the elements incorporated by composers in their compositions often undergo several transformations. After being processed to show a personal style, the original material is often not easily recognizable to the listener. However, he believes that the audience's understanding of a work is not based solely on the referentiality of the music, but rather on the overall aesthetic expression and accessibility of the piece. So even if one cannot fully capture the composer's hidden message in the music, it does not detract from listeners' appreciation of the work. Therefore, to certain extent, the origin of the material or inspiration used by a composer in a work does not have the same significance for the composer as it does for the listener. Hsieh holds an open-minded attitude towards how listeners interpret his works, believing that the abstract nature of musical expression gives the audience more room for imagination and allows for unique understandings by individual listeners.

Currently teaching in the U.S., Shih-Hui Chen talks about how she encourages her students to proactively draw from the musical traditions of their own cultures of origin during composition class when she meets students from Taiwan or other Asian countries. She believes that some of the young composers in Taiwan today grew up in an environment where it was difficult for them to naturally come into contact with traditional arts, and that the lack of relevant training in their upbringing may have caused them to feel unfamiliar with traditional music and indirectly discouraged them from incorporating traditional elements in their compositions. Chen understands this hesitation, but she believes that since we can speak and understand Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and Mandarin, even if we had fewer opportunities to get close to traditional music in the past, as long as we are willing to try, we should be able to gradually build up the relevant skills in the future. She uses her own experience as an example. Although she was exposed to traditional theatre when growing up, she didn't think about how to apply it to her own works when she was younger and her knowledge was limited. However, after nearly 40 years in the United States, her mindset has gradually changed as she identifies more and more with Taiwan. She has come to realize the importance of learning about traditional culture. She is happy about the trend of an increasing number of works focusing on local cultural traditions. She believes that starting from one's own cultural traditions is a vital contribution that Taiwanese composers can make to the development of contemporary music around the world.

Conclusion

When the first generation of Taiwanese composers used traditional and local elements in their works, their motivation was not only to draw from their own culture and pursue Eastern aesthetic concepts and thinking, but also to create music that could represent Taiwan across national boundaries because of their own devotion and sense of mission for their homeland. Through the efforts of their predecessors, today's Taiwanese composers no longer need to shoulder the heavy responsibility of vying for the international stage with their music. Instead, they focus on the local customs, culture, history, and traditions of the different ethnic groups in Taiwan from a purely personal standpoint, showcasing diverse musical perspectives and allowing for the fusion of the traditional with the contemporary, East and West. Many traditional cultures have gradually vanished with the transformation of society, and through music creation, composers do not aim to reproduce or preserve their heritage, but rather to reimagine traditions and explore new possibilities, sharing with audiences the richness and diversity of Taiwanese music.

*Translator: Linguitronics

More OUTLOOK