In the 16th century, Basilica San Marco had its platform and two organs in symmetry while the musicians and choirs occupied different lofts and the sounds they created scattered, which eventually resulted in the “polychoral style” of a surround sound featuring successive and contrasting musical lines. In the 19th Century, Friedrich Nietzsche received his writing ball, a globular typewriter, on which he wrote his Also sprach Zarathustra, known for its subversive writing style distinguished from all his previous works as it gathers a myriad of short and fragmented paragraphs as well as lyrical maxims. Artistic practices, no matter what specific field we are discussing, are never pure spiritual activities, but closely related to the physical situation they inhabit and the development of media technology such as the use of different tools and techniques. “The medium is the message,” says Marshall McLuhan, and how media can be seen as the extension of human organs or consciousness has become a popular topic in the art and cultural studies of Taiwan.

In Taiwan, the vigorous contemporary music scenes also see multiple influences coming from the development of media technology – often in the forms of electronic media, new technologies, or scientific research achievements – to encourage and stimulate new and interesting creations. However, a short article like this is far from sufficient to provide a comprehensive and detailed description of all its developments and current practices. Instead, I would like to select several interesting cases from the NCAF Granted Project Database and to re-explore these contemporary music projects from the media perspective as an alternative approach.

Let us begin with “electroacoustic techniques,” the most important media technology in contemporary practices. The technique has a lineage from John Cage’s experiments with turntables, Pierre Schaeffer’s recorded materials for synthesis sounds, to Iannis Xenakis’ promotion of electronic music, and now it has eventually become a common scene in contemporary music. Indeed, its genealogy is complex with multiple entry points including serious music in academia, sound scores in theatre, to sound art in its broader definition (which can also be divided into academic, performance-based, and underground practices).[1] If we put aside its genealogy for a moment, there are two media-oriented lineages which deserve our attention.

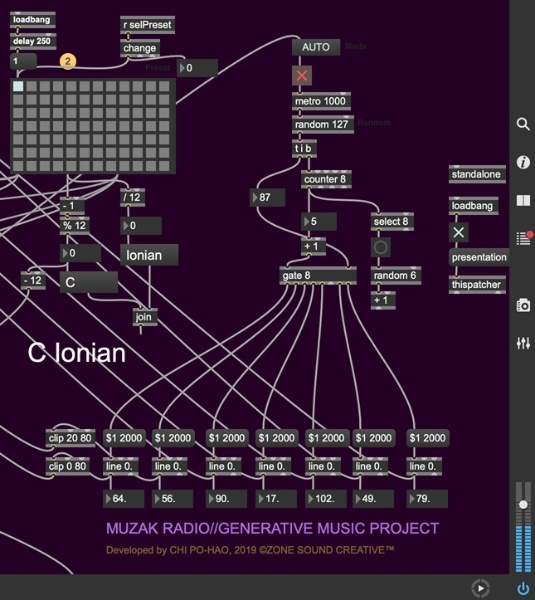

The first is how the electronic device has been given increasing creative subjectivity from a passive carrier as it used to be to become equivalent to the artist. In conventional music writing, the composer conceives the work in one’s brain before it is written as sheet music or played on instruments. It is a unidirectional approach from “conception/imagination” to “realization.” However, with the advancement of digital technologies, electronic programs or devices now have the abilities to detect, receive, and analyze the sound/music produced by performers, before it reacts immediately and aptly in its response and re-creation. The creative process is like a dialogue with another clever artist, presenting a two-way communication between the “composer/performer” and “electronic program/device.” Sandra Tavali (Wuan-chin Li)’s Duet in Autumn and In a Soundscape No.2 are two examples combining conventional instrumental music and electroacoustic feedback. The former, presented at the 2018 NYCEMF (New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival), is a music piece with a piano interacting with computer-generated sound, while the latter is for an oboe and the interactive electroacoustic system. Similar approaches can be found in Cheng Chien-Wen’s and Cheng Nai Chuan’s compositions commissioned by Taiwan Computer Music Association for the event "Electro- Pop" – The Experimental Pop Presentation. Meanwhile, Chi Po-hao in his Elevator Music Generator reconstructs the composition method to depend on algorithm and daily automatically adjusted parameters to create music which never repeats itself. By doing so, the creation is independent from a preset composition framework, which is no longer necessary. These experimental creations fundamentally challenge the authoritative status which used to belong to composers and open up a co-creation model for contemporary practices.

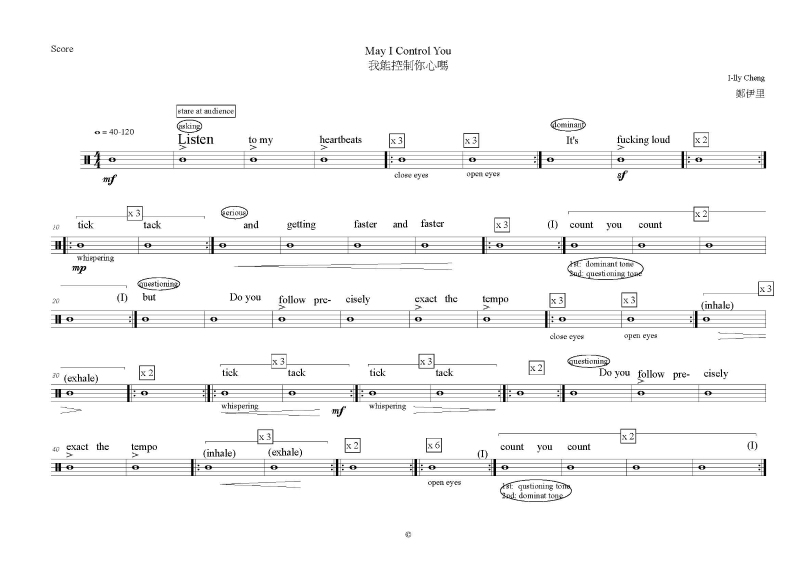

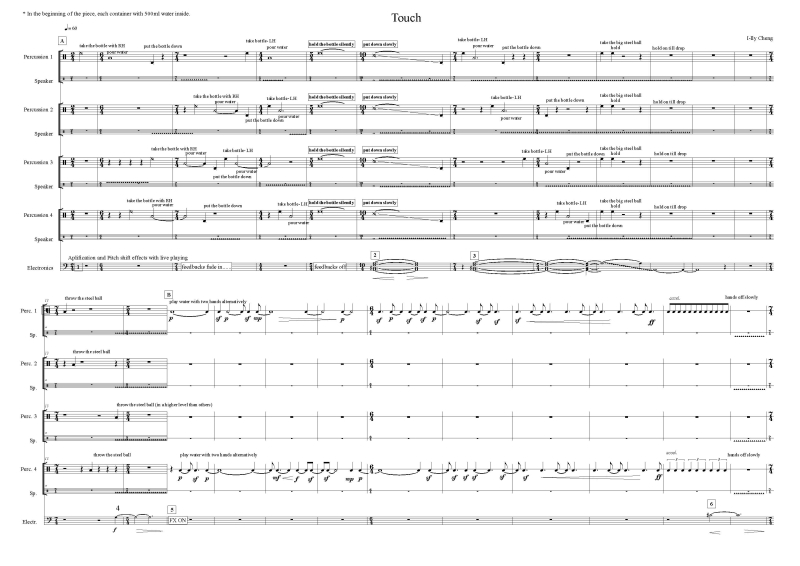

The other lineage is closer to the approach adopted by the great composer Alvin Lucier, the author of I Am Sitting in a Room, and it involves the artist creating unique sound installation for performance or exhibition. Examples in this category include sound artist Wang Chung-Kun, who is known for his sound and kinetic installations to transform abstract sound into concrete movement. In his earlier solo exhibition [+-*/] Wang Chung-Kun Solo Installation, the electromagnetic air valves click open to simultaneously create sounds and air vibration, juxtaposing what one hears (the sound) with what one’s skin feels (the air). His recent exhibition Sensational Flow employs the aerodynamic installation, which makes sound as triggered by visitors’ every movement to create a unique and interesting “human-and-device” interaction. Dedicated to live performance, composer Cheng Ily turns installations into instruments in her creations, usually with a careful attention to the trivial variations and interaction in its expressive nuances. In May I Control You?, Cheng uses the computer to control the fake heart, fake blood, and pump motor, while the performer delivers a soliloquy to invite the audience to listen to the heartbeats, musically demonstrating the dialectical relation between freedom and control. As for her Touché Nature for four percussionists/water installations, the speakers produce sound to vibrate the water while performers use different ways to stir the water in the basin. The signals interact with each other to form a multi-subject network between humans and devices.

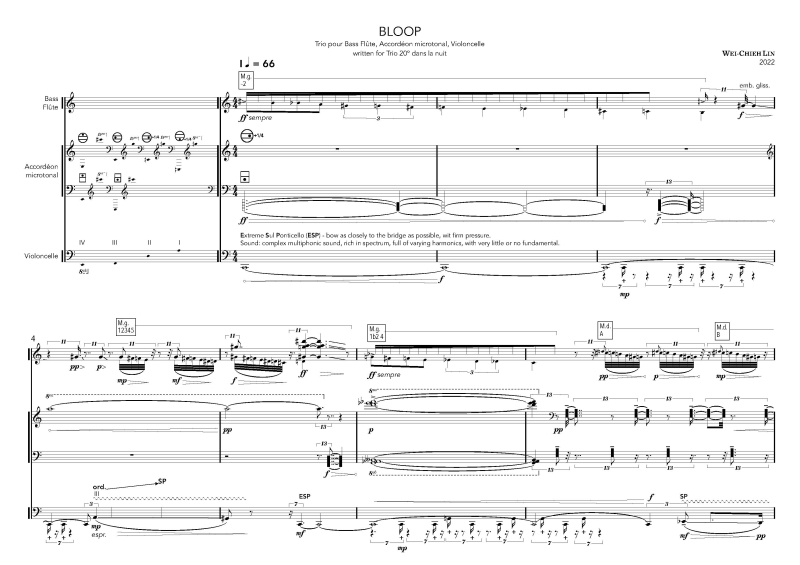

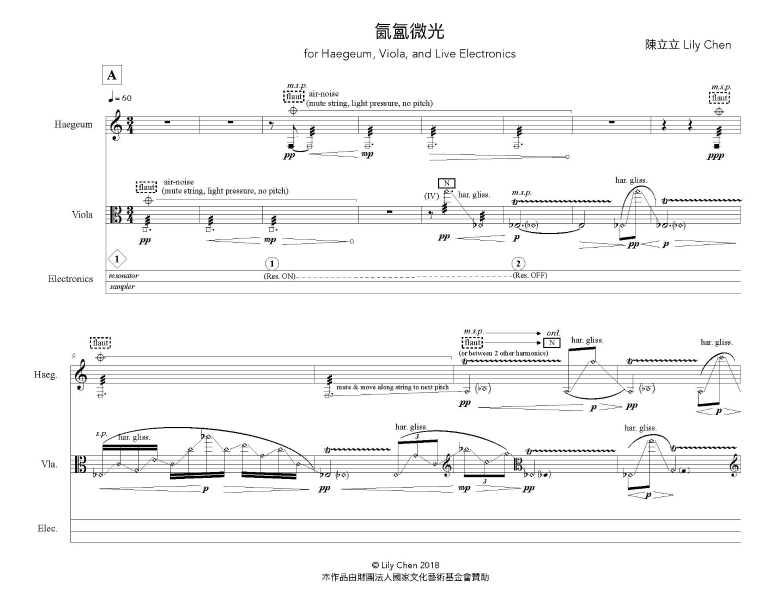

In addition to the abovementioned practices using new techniques to make sounds, media can reach the spiritual mind and consciousness to inspire artists. To be more specific, the invention of gramophones liberated sound from symbol-based notations to be recorded in its purer form. The concept to “keep the sound as it is” has inspired many artists to adopt a more direct approach to reproduce the sound as it is, acoustically imitating what is heard via composition, instrumental techniques, or installations. Lin Wei-Chieh’s BLOOP is a trio for bass flute, microtonal accordion, cello, in which he imitates the “blooper” sound of guitar (a looper pedal effect) to make variations of the repeated melody, creating special effects of changing timbre, articulation, and collage. In Lily Chen’s creation and promotion project Shimmering in the Air: for haegeum, viola, and live electronics, the composer uses instruments to imitate the sound of the air, while the real-time response from the resonator transforms the sound materials produced by the air flow into fine and beautiful moments of life.

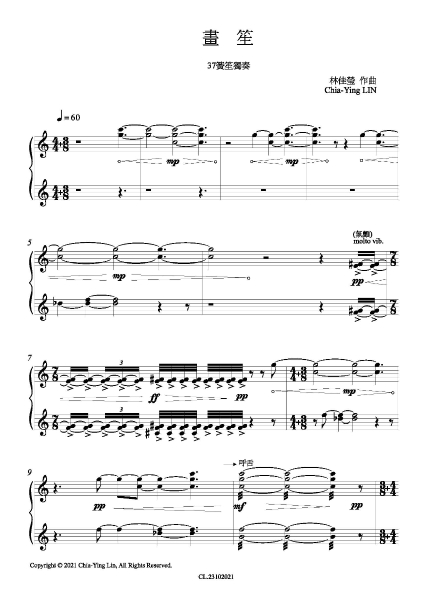

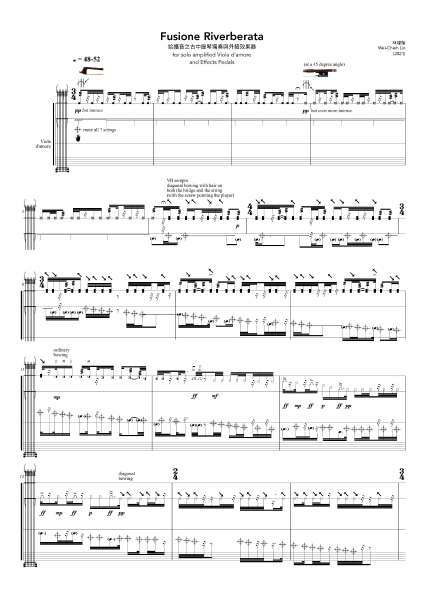

Sometimes, the use of media allows the artist to reexamine how “instruments” function as intermediary devices to make musical sounds and to challenge the conventional ways of playing certain instruments to rediscover new and different possibilities. As for academic research, we see projects such as “Notation in Contemporary Pipa Music” by Su Yun-han and “A Composition for Sheng Solo and the Development of Instrumental Diagram” by Lin Chia-ying, which respectively document and analyze the new instrumental techniques, notations, and lineage of pipa and sheng as a tool book for the promotion of and creation for traditional instruments. Another example is Lin Wei-chieh’s “A Transnational Research Project on Viola d’amore,” in which he works with an international musician of viola d’amore to study its instrumental techniques and to set up a database listing all the modern techniques and repertoire they have gathered. Under his project “Resonance of viola d’amore,” he also completed the experimental music piece Fusione Riverberata for solo amplified Viola d’amore and Effects Pedals as a perfect integration of the early musical instrument and contemporary music.

The aforementioned artists and creative approaches, though great in number and diverse in practice, are just the tip of the iceberg in comparison to Taiwan’s vigorous contemporary music scene as a whole. For those who are interested in this topic, the NCAF Granted Project Database is always ready for service with its “Composition” section (especially in the category of “electroacoustic music”) to offer an in-depth knowledge concerning the composer’s background, their creations, and the current trends of Taiwan’s contemporary music/sound art.

References:

[1] Muching, Wu. “聲音場景-台灣:2000–2010聲音藝術/音樂的「分立』與「返照」” [The Sound Scenes of Taiwan between 2000 and 2010: The Division and Reflection of Sound Art and Music]. ITPARK. (http://www.itpark.com.tw/people/essays_data/683/1011)

*Translator: Siraya Pai