Place

Li Zishu's (黎紫書) novel Land of Mundanity (流俗地, 麥田出版/Rye Field Publishing Co., 2020) begins with a tantalizing mystery: a character named Dahui (大輝), long presumed dead, shows up on a main thoroughfare of a town called Xidu (錫都, Tin Capital). After reading this novel's very short opening paragraph about a "dead" character's strange reappearance in broad daylight, questions quickly arise in readers' minds. Who is this man? Is he the same person as the one thought dead? What did he do, and where has he been? Why has he returned?

Contrary to what might be expected, the next paragraph does not elaborate Dahui's backstory or the circumstances surrounding his arrival. Instead, it launches into a detailed description of "Tin Capital" itself. The street on which Dahui returns leads to a part of the city that features some of its most remarkable features, namely, limestone hills and precipitous cliffs, which house historic cave temples: Sam Poh Tong Temple (三寶洞), Nam Thean Tong Temple (南天洞), Ling Sen Kuan Yin Tong (仙岩觀音洞). It seems Dahui's appearance, strange and intriguing though it may be, is in fact a red herring, its significance diminished amid rich descriptions of the dramatic landscape.

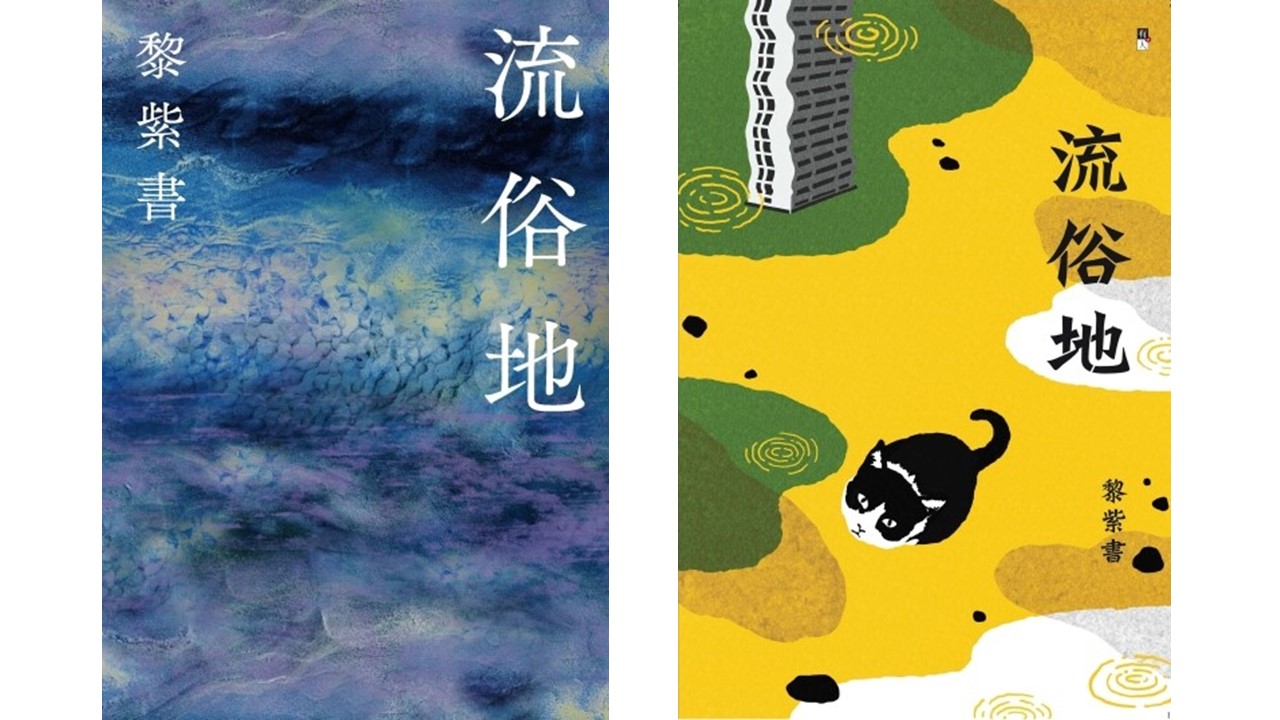

Li Zishu's (黎紫書) novel Land of Mundanity (流俗地).

What these opening paragraphs efficiently make apparent is that the more important character here is the city of Xidu itself; the reference to tin, coupled with the novel's early thick descriptions of cave temples, certainly bring to mind Li Zishu's hometown of Ipoh. Ipoh is the capital of the state of Perak, which stretches between Selangor and Penang on peninsular Malaysia's west coast and is situated at the heart of the Kinta Valley. Long revered for its limestone cliffs and extraordinary cave temples, it also became one of the richest tin mining regions in the world. Ipoh's modern development originates in the late nineteenth-century Kinta Tin Rush, which first attracted a wave of immigration from China's southern provinces and then the British colonizers. As tin mining spurred the development of infrastructure, Ipoh grew into one of the largest cities in the Federated Malay states. Modern Ipoh consists roughly of two districts, separated by the Kinta River: Old Town, known for government buildings and impressive colonial architecture, and New Town, the development of which was started in 1905 by a Hakka miner and entrepreneur named Yau Tet Shin (姚德勝, 1859-1913).

Much of the literary pleasure I initially derived from Land of Mundanity stemmed from the fact that its myriad "real-life" references allowed me to experience Ipoh and absorb its history and culture as an "armchair" or virtual tourist. Not long after the cave temples, for example, we encounter Hugh Low Street (修羅街)—now known as Jalan Sultan Iskandar—one of the oldest streets in Ipoh named after Sir Hugh Low (1824-1905), the third British Resident of Perak (1877-1889)1. Later, we come across "Concubine Lane" (二奶巷), reputedly purchased by Yau Tet Shin for his multiple wives, Ipoh's own "Salted Fish Lane"(鹹魚街), and signature drink, "white coffee" (白咖啡). Some of these Ipoh landmarks and cultural features I recognized from my own travels; others I enjoyed learning about from an array of travel bloggers and Youtubers (two examples: Concubine Lane video; and Ipoh Old Town walking tour, narrated in Mandarin). I took similar pleasure reading Li Zishu's first novel Age of Farewell, (告別的年代, 聯經出版/Linking Publishing Co., 2010),2 which was also set in a fictional town called Xibu (錫埠), but which, again, frequently referred to distinctive Ipoh landmarks like the Night Light Cup (夜光杯, the fountain at the Sultan Yussuf roundabout, for pictures and more information, do your own Google search or visit this site in particular: https://traveltrain.blogspot.com/2016/08/blog-post_84.html).

Still, the insistence in the Land of Mundanity on the alternative name of Xidu continually reminds readers that we are exploring a world that may be strongly informed by Li Zishu's hometown of Ipoh yet remains a fabrication. Xidu is not a reflection of Ipoh, it is a refraction, having been altered by its course through Li Zishu's literary imagination onto the page. The more time I spend in Li Zishu's literary worlds, the greater my interest in how she approaches and thinks about the construction of place in her writing. I was fortunate to be granted an interview with Li Zishu while drafting this essay (generously facilitated by NCAF)3, and among my first questions was about her decision to use the name "Xidu" for Ipoh in her novels: why not just identify her settings as "Ipoh"? Her response shed light on why her narratives take pains to integrate more clearly identifiable landmarks and well-known historical features with invented names, why they strive to situate readers in a place that is simultaneously recognizable as Ipoh and yet not able to be reduced to Ipoh as an actual place. On one hand, being able to draw upon her knowledge of and experience in Ipoh is essential to her craft and feeling self-assured in her writing: “Because I feel that the details required by novels, those background details, are so numerous, I feel I want a place I am personally familiar with, so that when I start to write I have relatively more certainty, otherwise I'm the kind of person who will feel very lacking in confidence".4 Yet this same familiarity presents a challenge as well, because "there is also the problem that I am too familiar with the place of Ipoh. I don't want to be writing a 'documentary' when I write about Ipoh, [or] for the writing to be only in order to document [the city], I am not writing to document it".

The fabricated names become a way for her to remind herself of her freedom to be creative, to create her own literary version of Ipoh rather than simply recreate the city she knows so well: "While writing, I constantly talk to and remind myself that 'this is a novel, is fiction, perhaps there is fabrication, you can make things up, you can absolutely make things up, even considering the place you are writing about comes from this place. It is not that this place may not be made up'". As we continue to talk, it becomes clear that, for Li Zishu, Ipoh is just a jumping-off point for a larger ambition: "But although my novel takes Ipoh as its background, in the end what I want to write about is Malaysian Chinese society … in most of the novel the Chinese society is based in Ipoh, but it reflects the history and situation of the whole of Malaysian Chinese society".

This takes us to an even more important and distinctive location in the novel: Upstairs Tower (樓上樓), a twenty-story public housing development near the Kinta River in a corner of Old Town that was once the tallest building in Xidu, hence the name Upstairs Tower (34). Before delving deeper into this location's special qualities and significance, let's first talk about how the novel leads us there; for this we must return to the novel's human characters and underlying structure. The person who first registers the "strange return of a dead man," mentioned at the start of this essay, turns out to be a blind woman named Yinxia (銀霞), who works as a dispatcher for Xidu Wireless Taxi (錫都無線德士); she fields a request for a taxi from a man whose voice and unique accent when speaking Cantonese she immediately recognizes as that of Dahui, who disappeared roughly ten years prior, having been driven from his home after an incident of domestic violence. And while Dahui's situation may continue to pique readers' interest, we have now become acquainted with the character who is the heart and soul of the novel: Yinxia. Yinxia is able to so quickly identify the owner of the voice on the phone in part because of her acute hearing and memory, but also because she knows the voice so well; Dahui is the older brother of one of her best friends growing up in the public housing development known as Upstairs Tower.

Thus does a deceptively straightforward set-up of Yinxia fielding a taxi request from a long-disappeared, presumed dead, notorious former neighbor result in readers being guided through the lives of the diverse community of ordinary, working-class Malaysians who call Upstairs Tower their home. Though ultimately Yinxia is the novel's main character, both she and Dahui can be seen as complementary nodes in a social network that grows from Upstairs Tower, the members of which we get to know through their connections with Yinxia and presumed interest in Dahui's fate. True, by the time of the novel's present most of the characters have moved on from Upstairs Tower, having improved their economic circumstances and climbed up a rung or two on the economic ladder. But we are granted access to this community largely through Yinxia's memories of having grown up in Upstairs Tower, which have been triggered by her recognition of Dahui's voice.

First, we meet Xihui (細輝), Dahui's younger brother and one of Yinxia's best friends growing up: he is the first person Yinxia calls upon suspecting that it is Dahui who has suddenly returned, and she reaches him while he and his wife are working at the convenience store he owns. As the novel proceeds, Yinxia's recollections of childhood lead readers to become acquainted with Xihui and a host of other fascinating characters and their life-stories. For example, we learn about Dahui's father, nicknamed Entsai (奀仔), a truck driver whose death—his truck went off the side of a cliff while he was driving through the Cameron Highlands (金馬崙) on a rainy night—suddenly turned Dahui, still a teenager at the time, into the head of the family; and Dahui's paternal aunt, Lianzhu (蓮珠姑姑), who comes to the city from a fishing village and ends up as the mistress (or concubine) to a wealthy politician.

We also come to know Yinxia's other best childhood friend: a Malaysian Indian boy named Lazu (拉祖), whose father owns a barbershop on the first floor of Upstairs Tower, with whom she and Xihui play chess and other games, and who instructs her in the beliefs related to the Hindu god Ganesha/Ganesh (迦尼薩); Lazu grows up to be a lawyer, following in the footsteps of his idol, Karpal Singh (卡巴星), a famous Malaysian politician and lawyer dubbed "the Tiger of Jelutong" (日落洞之虎) for his fierceness and willingness to take on controversial cases and oppositional stances over the course of his career. I also found myself captivated by the life-story of a woman known as Mapiao Sao (馬票嫂, Horse-racing Lottery Sister), idolized by Yinxia for her mastery of the mammoth Tua Pek Kong's Thousand Pictorial Dictionary (大伯公千字圖) and her ability to befriend everyone in Upstairs Tower; having escaped hunger and poverty in her first marriage only to then have to contend with disdain and abuse from her husband's family, Mapiao Sao manages to eventually find stability and happiness in her second marriage to an aging triad member who proves fiercely loyal to her. This is just a sample; by the novel's end, readers have encountered a vast array of intriguing, richly drawn characters representing all walks of working-class life in Malaysia as well as myriad facets of the human experience.

As Li Zishu observed, upon being asked about her decision to use locations like the Mayflower Hotel in Age of Farewell and Upstairs Tower in Land of Mundanity, "Many Malaysian Chinese authors, like those Malaysian Chinese authors based in Taiwan, when they are writing a Malaysian background, they all like and are accustomed to writing about tropical rainforests and rubber forests, these types of places" (16:14-16:27). For Li Zishu, this can create the impression in the minds of non-Malaysian readers that, in Malaysia, "everything is forest, rainforest, or kampung (a rural village in Malay) countryside" (16:30-16:41). It also falls outside her own experiences living in Malaysia: "I myself did not grow up in those kinds of places, actually I have never been to the rainforest", and while she has some familiarity with rubber forests on her mother's side, she herself grew up in Ipoh's urban environment (16:41-17:04). Li Zishu also explained that she was working as a journalist while writing Age of Farewell, and that her portrayal of the Mayflower Hotel, its residents and environment, captured her feelings toward Ipoh at that time, its continued existence amid declining fortunes: "My sense of a place like Ipoh is actually closely connected to my description of the Mayflower Hotel: it is on the wane and has been abandoned, but it continues to eke out an existence. Many of the people who come to the hotel are down on their luck and live there in their declining years, and I also think that this environment was like the feeling I got from Ipoh at that time."

As a reader, I found myself equally moved by the Mayflower Hotel and Upstairs Tower, and how both locations focus attention on—thereby assigning value to—the lives of people grappling with economic and other forms of marginalization. But I have also been struck by how the Upstairs Tower location in Land of Mundanity facilitates an exploration not just of economic hardship, but also of community formation and coming of age within Malaysia's profoundly multicultural society. Here let me return to Li Zishu's illuminating reflections on her decision to center her novel around this sort of public housing complex:

|

|

While writing Land of Mundanity, I wanted to write Ipoh. I knew that what I wanted to write was not just Ipoh, what I wanted to write was Malaysian Chinese society as a whole. So I thought if I want to write about this society, I wanted to find a concentrated place that could present the atmosphere and feeling of this society. So, I thought of this Upstairs Tower, this public housing complex, where people from the major ethnic groups (in Malaysia, i.e., Malays, Chinese, and Indian) all live together. But they have been forced [to live there], they have no choice, because it is only (because of) poverty that they live in a place like Upstairs Tower, and no one has a choice but to live in that kind of place, moreover, every major ethnicity, every cultural element is there …. (And also) because the place where I went to school when I was young was very close to this kind of public housing complex, Kinta Heights, it was very close, I frequently had the chance to see it and run around there … as a result it made a very deep impression on me, and I am very familiar with it. So I thought, eh, I could compress all of Malaysian society into this public housing complex and write about it from there. |

Memory

As important as place is for Land of Mundanity, equally important is memory and the temporal elasticity that goes with it; I have long been interested in the use of memory in Li Zishu's fiction, for example, in early stories like "State Capital Chronicles" (州府紀略) "Night Journey" (夜行) and "Mountain Plague" (山瘟) (discussed in Chapter 7 of my book, Sinophone Malaysian Literature: Not Made in China [Cambria Press, 2013]). While the contours of the distinct community evoked in Land of Mundanity come, narrowly, from Upstairs Tower, and Xidu, more broadly, its substance manifests in characters' memories, and via the "memory organ" itself. By facilitating rapid trips back and forth through time, particular memories create intimacy between readers and characters and provide insights into characters' personalities and lives. The novel's opening chapter trains its readers to grow comfortable with temporal shifts spurred by the act of remembering. Above I talked about how the peculiarity of Dahui's supposed return fades into the background of the detailed descriptions of the location from which he calls the taxi company. Closely following this are equally detailed descriptions of the timing of his return: in September, coinciding with the Hungry Ghost Festival (中元節) and at the beginning of a month that feels terribly long because of its unusually high number of public holidays, starting with National Independence/Merdeka Day (國家獨立日) on August 31, followed by Eid al-Adha (哈芝節), and then "Malaysia Day" (馬來西亞日).

It is during this five-day public holiday that Yinxia recognizes the voice and unique accent of the person who has called in requesting a taxi—and is subsequently transported by that voice back in time to her childhood and to where she grew up, Upstairs Tower. When Yinxia clarifies that the caller wishes a taxi to take him to "Old Town" (舊街場), he replies in Cantonese in such a way that makes Jie (街) sound like Ji (雞), triggering Yinxia's memory of Dahui's distinctive accent: how she and Xihui would make fun of Dahui behind his back, especially when Xihui was upset after having been punished by Dahui, who had to take on the father's role after their father's death. Thus has the narrative meticulously established both the geographical and temporal setting while simultaneously making clear that Dahui is important less for his own sake than for the community he came from. Readers also finish the opening chapter having been trained to expect rapid shifts back and forth in time as the narrative presents its characters, fills in the substance of their personalities and memories, and characterizes its community as a whole. And while the novel's closing chapter takes as its backdrop the momentous 2018 national election, which ended over sixty years of Barisan Nasional rule and brought down the government of Najib Razak, it yet maintains the strict focus on the ordinary, yet rich and full lives of Yinxia and the working-class community of which she is a part.

Perception

Another of my longstanding interests in Li Zishu's fiction is her tendency to construct her evocations of Malaysian communities around powerful female characters, and Land of Mundanity is no exception. I've already touched upon the structural importance of the Yinxia character for introducing readers to her community, but what about her blindness? What does it mean that our means of entry into the setting and community of Land of Mundanity is from the perspective and through the memories of a taxi dispatcher who happens to have been born without sight—and yet possesses an extraordinary knowledge of the city?

When I asked Li Zishu about this character, I was interested to learn, first of all, that the character is rooted in Li Zishu's experience of daily life: returning to Ipoh for visits while living abroad, she did not have her own means of transportation so became accustomed to calling for taxis. After a while she realized she was always hearing the same woman's voice when she called, and "After I had called for a car many times, she became very familiar with my voice, as soon as she heard my voice she knew my address and what I wanted … it was as if there was a strange connection there". These ordinary, mundane encounters then sparked Li Zishu's literary imagination, causing her to wonder about the woman herself—"I started having many fantasies, thinking about this woman, how she made a living, what her job was like" —and her relations with the taxi drivers—"I couldn't help asking those taxi drivers about this character, this woman-on-the-wire, what is she like, how do you normally communicate, have you seen her face? Chatting with them like this". Li Zishu was also struck by the woman's impressive knowledge of the city: "The extent of her familiarity with the city was such that, even if it was a very small place, [she would say] 'how about you go to that 7-Eleven to wait,' it was as if she knew all the landmarks of that place that she had probably never been to [herself]". Eventually she began to realize the value such a character would have for writing about the city: "To take this city, Ipoh, as a background, I think this character would be highly effective, she could really express my intentions".

I was also struck by Li Zishu's comments on the broader effect or value of a blind character like Yinxia who cannot see the differences in people that can seem to perplex—or distract—those of us with sight:

|

|

This character of blind woman in reality truly cannot see this city. She truly cannot see all the people, cannot see difference, cannot see east-south-west-north, cannot see the self-proclaimed differences of people like skin color or religion or these things, she cannot see these things, all that which most befuddle us: the various prejudices of people—these have no effect on her because she does not see, she has no visual perception, her way of judging the world, her way of identifying people, are perhaps different from those of us who can see. |

Above I mentioned the pleasure I derived from how the novel escorts me through an entrancing fictional version of Ipoh, and then guides me to the even more captivating location of Upstairs Tower, its vibrant community, and the life-stories of its members. It would be very remiss of me not to stress as well how much I enjoyed experiencing these places and people in the company of Yinxia, and I am confident I am not alone in this. So much can be said about Yinxia as a character, and her embodiment of qualities such as strength, kindness, and resolve—particularly in the face of challenges that, as we learn over the course of Land of Mundanity, extend well beyond having been born blind into a hard-working, but still impoverished, family. I do not want to tell other readers how to feel about Yinxia, or how to think or feel about any other character or aspect of the novel, for that matter. I just want to close this essay with a note of gratitude: I feel fortunate to have spent time exploring the streets and people of Xidu, and the community of Upstairs Tower, in the company of Yinxia and her cohort. They have broadened my horizons and enriched my world immeasurably, and I am all the better for it.

文章作者介紹

Alison M. Groppe

Alison Groppe 古艾玲 is an Associate Professor of Chinese in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures in the School of Global Studies and Languages at the University of Oregon, where she teaches courses in modern Chinese and Taiwanese literature and film. She specializes in literary and cinematic representations of identity, Sinophone Malaysian and Singaporean literature and film, world literature, and is currently working on a book manuscript about Sinophone Malaysian women writers, including Li Zishu, and literary infrastructure. Her publications include Sinophone Malaysian Literature: Not Made in China (Cambria, 2013); "Sound, Allusion, and the 'Wandering Songstress' in Royston Tan's Films," in Chinese Cinema: Identity, Power, and Globalization (Hong Kong University Press, 2022); "Gu Hongming's Journey from British Malaya, via Europe, to China and the Confucian Classics" in A Companion to World Literature (Wiley-Blackwell, 2020); "2008: Writer-Wanderer Li Yongping and Chinese Malaysian Literature," in A New Literary History of China (Belknap Press, 2017); and "Coming of Age and Learning to Live (with Ghosts) in Borneo's Rainforest," in Coming of Age in Chinese Literature and Cinema: Sinophone Variations of the Bildungsroman (forthcoming from Amsterdam University Press). Alison received her PhD and MA degrees from Harvard University, and her BA from Wellesley College. Her literary research trips to Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia have been generously funded by grants from Taiwan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the US Departments of Education (Fulbright-Hays DDRA) and State (Cultural Exchange Fulbright [Taiwan]).