The recent years have seen the emergence of “curating” as a trendy term in performing arts. Borrowed from the visual arts, “curation” originally referred to a museum position to take care of its collection. In the 1960s, with the rise of performance art, body art, live art, and happening, “curation” also expanded its realm from material exhibits to the immaterial media such as body and live performance. The curatorial practice and position were introduced to the contemporary dance scenes in Europe to replace terms such as “artistic director,” “producer” or “programmer” in the 1990s, while a similar transition followed in Taiwan, as shown in the NCAF Online Grant Portfolio Archive that between 2013 and 2016, there were only one or two “curatorial project(s)” annually in the regular grant list but the number increased to 4 or 5 after 2017.

Curating as Programming

The most common curatorial approach in dance found in the Grant Portfolio Archive is to put several productions together and to conceive a theme which connects all for marketing purpose and providing an integral narrative for the program, as a continuation of how “Dance Collection” and “Dance Festival” used to operate. Similar examples include “New Choreographer Project” by MeimageDance featuring overseas Taiwanese dancers to “choreograph at home,” “CoDance Festival” by SunShier Dance Theatre which brought choreographers of different generations together, the biennial or triennial transnational micro-dance festival “Dance Round Table” by TTCDance, “Want to Dance Festival” by Shinehouse Theatre staged at unconventional spaces in the historic Wanhua district, and “Next Choreography Project” by Shu-Yi & Dancers as a platform for young emerging choreographers.

This approach is more like the programming of various dance productions together, and it mostly invites and presents conventional dance pieces, thus showing little difference whether it is under the work of a curator or an artistic director. The curatorial concept is often proposed to polish the program, especially for the organizer to promote the event more effectively through such an interconnection among different productions. Since the purpose is to connect, they will also invite the artistic directors, curators, and producers of major festivals or venues to establish and strengthen the network in production and marketing.

Curating as a response to the problematique

However, since 2016, the NCAF Grant list has shown a different approach to dance-curating: the curator would first propose a certain problematique, and then invite artists from different disciplines to explore or respond to the raised topic via performance, workshop, lecture, idea exchange, or work-in-progress. Their curatorial practice is to adopt dance and body as a medium to investigate the chosen topic, be it a specific issue or something interesting to be developed, and to collectively produce a response which is highly sensorial, experimental, dynamic, and organic.

In this case, we see “Primal CHAOS - Dance X Sounds Improvisation” organized by HORSE exploring how body and sound improvised for an intuitive encounter, and “Body Archipelagos” by Bare Feet Dance Theatre where body became a point of departure for theatre companies, independent artists, and writers to gather and to develop a body-oriented interdisciplinary momentum and discourse. Meanwhile, “Back to the moment Dancing Talking Bar,” another project by HORSE, invited senior dancers, choreographers, and critics to join in the screening of the recording of past performances, followed by an in-depth conversation with a purpose to revisit and recontextualize the history of the Taiwanese dance scenes. The Pingtung-based Tjimur Dance Theatre started Tjimur Arts Festival to further its work with the local cultural communities in the indigenous tribes in the Sandimen area as it brought people of various professions from dance, cuisine, agriculture, to craft together.

“Seeing the Unseen - A Site-specific Creation Project” was another attempt by Bare Feet Dance Theatre which walked away from conventional stage to open up a contextualized conversation between the body and the environment, while Dancecology’s “Contours - Dance Film Exhibition,” featuring dance videos from both Taiwan and Australia, also touched upon the environment but it aimed to reflect on the reciprocal relationship between humans and ecology/nature.

Interdisciplinary Curating

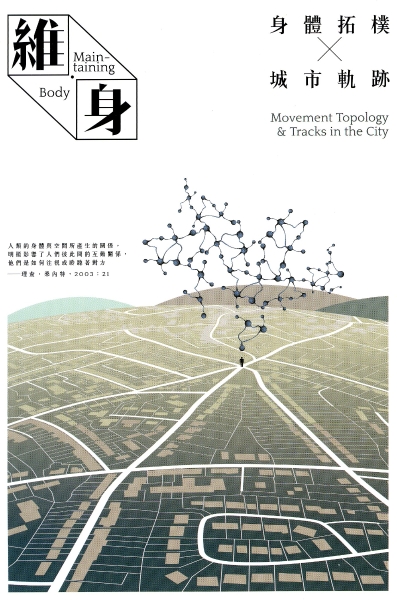

There are also projects exploring other possibilities of curating contemporary dance in the aspects of research, theory, and history: the choreographer Lo Wen-Chun participated the NCAF’s Curator's Incubator Program @ Museums, through which she collaborated with the new-media artist Wang Lien-Chang to visit France for a research on performance art and the contemporary choreography in Europe in the 2014-2015 project “‘Maintaining _ Body’ Movement Topology & Tracks in the City.”

In Dancing Museums: Research on Interdisciplinary Performance, the dance scholar Chang I-Wen traced it back to the experimentations by Judson Church and minimalist art in the 1960s to study how dance is related to performance art and live art, as later published in her essay “Choreographing Exhibitions: Performative Curatorgraphy in Taiwan” which could be read in the NCAF electronic journal Curatography. “Digital Corporeality: Choreographing New Media Arts” was another research project conducted by Chang, with its first-stage research-in-residency funded by the NCAF’s Production Grants for Independent Curators in Visual Arts, in which she focused on “Choreography” and “Technological Phenomenology of the Body” to investigate the relationship between technological arts and the digital(ized) body.

The curatorial practices and research projects discussed above all employ dance and body as the medium for its ability to have an immediate reaction, physically and critically, to the time and space it inhabits, rather than simply a carrier of movements and emotions. Such a perspective thus expands the historical, political, and social dimensions of curating contemporary dance, as it increases its interdisciplinary reach. The curator Jo Hsiao included dance, performance, participatory art, online streaming, lecture performance, puppetry, document theatre, music, sound and video in Arena, organized by Taipei Fine Arts Museum, to create a loop of interplay between live exhibition and static display.

In “FW: Wall-Floor-Window Positions,” as a part of the ADAM Project by Taipei Performing Arts Center, the curator and performance artist River Lin invited choreographers and dancers in the time of the pandemic where arts could almost only take place online to reflect on how the Internet and online streaming had an impact on dance in terms of spatiality, performativity, and spectatorial co-presence. Re: Play at C-LAB, curated by River Lin, Chuang Wei-Tzu and Powei Wang was another example with the body as its point of departure, as it revisited the 1990s to focus on the body which appeared in the visual arts and little theatre in Taiwan. By examining the image of body in the 1990s, re-enacting and re-narrating the history, engaging daily spaces, and workshopping, it explored what the body could possibly indicate in our modern/contemporary society.

With the emergence of “curating” in Taiwan’s contemporary dance, it certainly deserves our continuous attention to expect how the Taiwanese choreographers, dancers, “body performers,” and dance researchers will develop their unique body-centric curatorial discourse and practice, which can further correspond to the wider Taiwanese context as a resonance or critique,

*Translator: Siraya Pai

-編舞(吳易珊)_6_1540878253161.jpg)

_1693364704555.jpg)